If preventive measures are not taken immediately floods will cause more damage.

Flood affected villagers with their belongings travel on a boat in Katahguri village in river Brahmaputra. (Photo: AP)

HIGHLIGHTS

- Assam falls under a meteorological zone that receives excess monsoon rains

- Brahmaputra carries a lot of water and sediments – another natural reason for floods

- Destruction of wetlands and encroachment of plains have worsened the situation

It’s tucked away in the inside pages of national newspapers, rarely makes it to prime time TV bulletins, hardly finds mention in the national discourse on development…floods in Assam are an annual affair, rarely raising more than an eyebrow.

As sure as night follows day, floods in Assam (and in most parts of the Northeast) follow the monsoon. This year has been no different.

According to data put out by Assam State Disaster Management Authority, till July 18 the death toll has touched 27 and is likely to go up. Over 4,000 villages in 28 districts out of the state’s 33 have been affected.

Assam’s population is just over 3 crore; of this 53.5 lakh-plus people are under threat. While close to 1,000 houses have been damaged, 88 animals have been washed away. Over 16 lakh animals, including livestock have been affected. Pictures of rhinos trying to reach higher grounds at the Kaziranga National Park surfaced on Thursday.

(Photo: Reuters)

Over 2 lakh hectares of crop land have been affected by the flood waters. Infrastructure — roads, bridges, culverts – and public utilities have also taken a hit.

Floods lead to loss in human lives and the economy takes a big hit. According to Central Water Commission data (1953-2016) on average 26 lakh people are affected every year in Assam; 47 lose lives, 10,961 cattle die, Rs 7 crore worth of houses destroyed and the total damage comes up to Rs 128 crore every year.

Why is Assam flood-prone?

There are both natural and man-made causes for the annual deluge.

Most of Assam falls under a meteorological zone that receives excessive rain during the monsoon season. According to the Brahmaputra Board, a central body under the Ministry of Jal Shakti tasked to monitor and control floods, the region receives rainfall “ranging from 248 cm to 635…Rainfall of more than 40 mm in an hour is frequent and around 70 mm per hour is also not uncommon”. There have been occasions when 500 mm of rainfall has been recorded in a day.

The valley through which the Brahmaputra flows is narrow. While the river occupies 6-10 km, there are forest covers on either side. The remaining area is inhabited and farming is conducted in the low-lying areas. Overflowing rivers and flowing rapidly down the valley tend to spill over when it reaches the narrow strips.

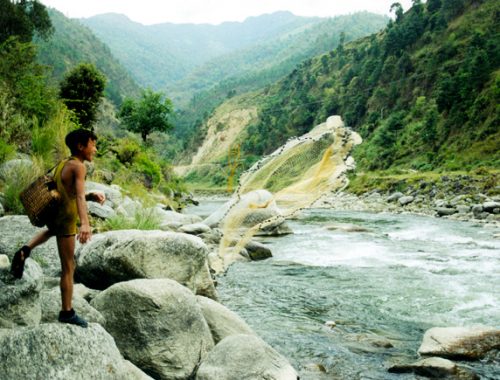

(Photo: AP)

The zone’s topography also complicates matters. The steep slopes force the rivers to gush down to the plains.

Assam lies in a seismic zone — in fact most of the Northeast does. Frequent earthquakes and resultant landslides push soil and debris into the rivers. This sedimentation raises river beds.

According to a paper published in the International Journal for Scientific Research and Development, “Brahmaputra water contains more sediments raising river by 3 metres in some places and reducing the water carrying capacity of the river.”

Then there are man-made causes that have worsened the flood situation. Encroachment is a big issue. The population density of Brahmaputra valley was 9-29 people per sq km in 1940-41; this shot up to 200 people per sq km now, according Brahmaputra Board.

The systematic destruction of wetlands and water bodies that act as natural run-offs have aggravated the flood problem in Assam. Though embankments provide protection, most of them have not been maintained leading to breaches.

Is there a way out?

First and foremost is the need for early warning systems. There are reports that around the Assam-Bhutan border, villagers form WhatsApp groups to warn people of rising water levels.

If such people-people arrangements can work out then there is no reason why more institutionalised systems, based on technology, cannot be put in place.

(Photo: AP)

These early warning systems should be institutionalised based on scientific approach.

Wetlands and local water bodies should be revived so that the natural drainage system can act as a basin for excess water to flow. This would entail clearing human encroachments in the Brahmaputra flood plains.

Embankments should be regularly checked for breaches and systems put in place for maintenance; a first step would be to break the babu-contractor nexus that finds floods an easy way to sponge money from the system. (India Today)