Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo of M.I.T. and Michael Kremer of Harvard have devoted more than 20 years of economic research to developing new ways to study — and help — the world’s poor.

On Monday, their experimental approach toward poverty alleviation won them the 2019 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. Dr. Duflo, 46, is both the youngest economics laureate ever and the second woman to be honored.

The three researchers study problems like education deficiencies and child health scientifically. They break issues into smaller questions, search for evidence about which interventions work to resolve them, and seek practical ways to bring those treatments to scale.

“In just two decades, their new experiment-based approach has transformed development economics, which is now a flourishing field of research,” the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said in a statement.

More than five million Indian children have benefited from effective remedial tutoring thanks to one of their studies, the release noted, while other work of theirs has inspired public investment in preventive health care.

Nobels have typically gone to more theoretical work. This year’s laureates distinguished themselves with work that is experimental and has immediate real-world impact. It shows that the field as a whole is approaching problems differently, a change that Dr. Banerjee, Dr. Duflo and Dr. Kremer have helped to bring about, their peers said.

Twenty years ago, “there was a lot of emphasis on economic theory, and more macroeconomic questions of development,” said Benjamin Olken, an economist at M.I.T. The Nobel winners broke those big questions into smaller problems and studied them like scientists running clinical trials.

“The approach has been tremendously influential in reshaping the field of development economics,” Dr. Olken said.

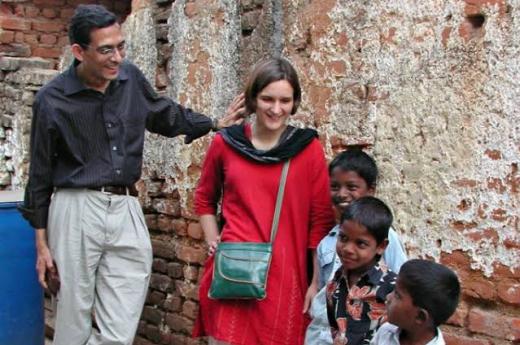

They have also worked to spread the approach. Dr. Duflo and Dr. Banerjee, who are married, in 2003 helped to found a global network of poverty researchers called the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, or J-PAL. The coalition helps to identify effective interventions — like deworming campaigns — and then works with governments and nongovernment organizations to implement them.

Speaking at a news conference shortly after learning of the award, Dr. Duflo said the award recognized the collective contributions of hundreds of poverty researchers.

“It really reflects the fact that it has become a movement, a movement that is much larger than us,” she said.

Who are the winners?

Dr. Banerjee, born in 1961 in Mumbai, earned his doctorate from Harvard. He is the Ford Foundation international professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Dr. Duflo, born in 1972 in Paris, has a doctorate from M.I.T., where she is the Abdul Latif Jameel Professor of Poverty Alleviation and Development Economics. Dr. Duflo won the John Bates Clark Medal from the American Economic Association in 2010, a frequent precursor to the Nobel.

Dr. Kremer, born in 1964, has a doctorate from Harvard, where he is the Gates professor of developing societies.

Reactions

The researchers’ peers were quick to applaud the prize.

“Congratulations to Banerjee Duflo and Kremer on the Nobel and to the committee for making a prize that seemed inevitable happen sooner rather than later,” Richard Thaler, who won the award in 2017, said on Twitter.

“Fabulous news!” Cass Sunstein, a co-author with Mr. Thaler on a book about behavior economics and a professor at Harvard, wrote on Twitter. He described a recent study by one of the winners as “profound, implication-filled.”

“The three of them have just been transformative in leading by example,” said Amy Finkelstein, a leading health economist, who said their research methods had helped to shape her own work. She works with the three winners through J-PAL.

“This is probably the first 21st-century prize in economics,” said Lawrence Katz, a Harvard economist. “We’ve given lots of prizes for the advances of the 20th century.”

“Their methods, and this is not stuff worked on 20, 30 years ago — this is stuff that, none of it started until the 2000s,” Dr. Katz said. “This really is 21st-century economics, and it’s wonderful that we’re moving into the 21st century with the Nobel prize, in my view.”

More about the research

The Nobel committee specifically highlighted a study Dr. Kremer helped write that looked at groups of school children in Kenya in the mid-1990s. It found that access to extra textbooks did not improve most student outcomes — showing the impediment to learning was not a simple lack of resources.

A subsequent experiment by Dr. Duflo, Dr. Banerjee and their co-authors identified a true barrier to student achievement: teaching methods that were insufficiently shaped to student need. Tutors for low-performing pupils in India improved achievement measurably, and lastingly. Dr. Duflo and Dr. Kremer have often written joint research, including guides on how to use randomized field experiments, the approach they champion, to study economic questions.

She and Dr. Banerjee collaborate regularly, publishing studies this year on “Using Gossips to Spread Information” — in which well-connected villagers were selected to spread information and increase vaccination rates — and using police resources to counter drunken driving in India.

The pair have a book, “Good Economics for Hard Times,” coming out in November, and they wrote an previous book, titled “Poor Economics.”

Who won the 2018 Nobel for economics?

William Nordhaus and Paul Romer, who have studied climate change and technological innovation, were honored last year. Professor Nordhaus, of Yale University, is a proponent of a tax on carbon emissions as a way to address climate change. Although he has convinced many members of the economics profession about the benefits of a carbon tax, the federal government has yet to adopt one.

Professor Romer, of New York University, was cited for demonstrating how government policy could drive technological change. He noted the success of efforts to reduce emissions of ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons in the 1990s.

Who else has won a Nobel Prize this year?

- The Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Abiy Ahmed, the prime minister of Ethiopia, for his work in restarting peace talks with Eritrea and restoring some freedoms in his country after decades of repression.

- The prize for medicine and physiology was awarded to William G. Kaelin Jr., Peter J. Ratcliffe and Gregg L. Semenza for their work in discovering how cells sense and adapt to oxygen availability.

- The prize for physics went to three scientists who transformed our view of the cosmos: James Peebles, a cosmologist, shared half of the prize with two astronomers, Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz.

- The prize for chemistry was awarded to three scientists who developed lithium-ion batteries: John B. Goodenough, M. Stanley Whittingham and Akira Yoshino will share the prize.

- The prize for literature was awardedto Olga Tokarczuk, a Polish author, and Peter Handke, an Austrian writer. Mr. Handke won this year’s prize, while Ms. Tokarczuk won the 2018 prize, which had been postponed for a year because of a scandal at the academy.

Jeanna Smialek writes about the Federal Reserve and the economy for The New York Times. She previously covered economics at Bloomberg News, where she also wrote feature stories for Businessweek magazine. @jeannasmialek