The politics and history behind France seeking ‘forgiveness’ from Rwanda for 1994 genocide

France’s partial admission of guilt is seen as part of an effort to mend ties with its former colonies and sphere of influence in Africa, where many still have painful memories of their subjugation, and continue to see French actions with suspicion.

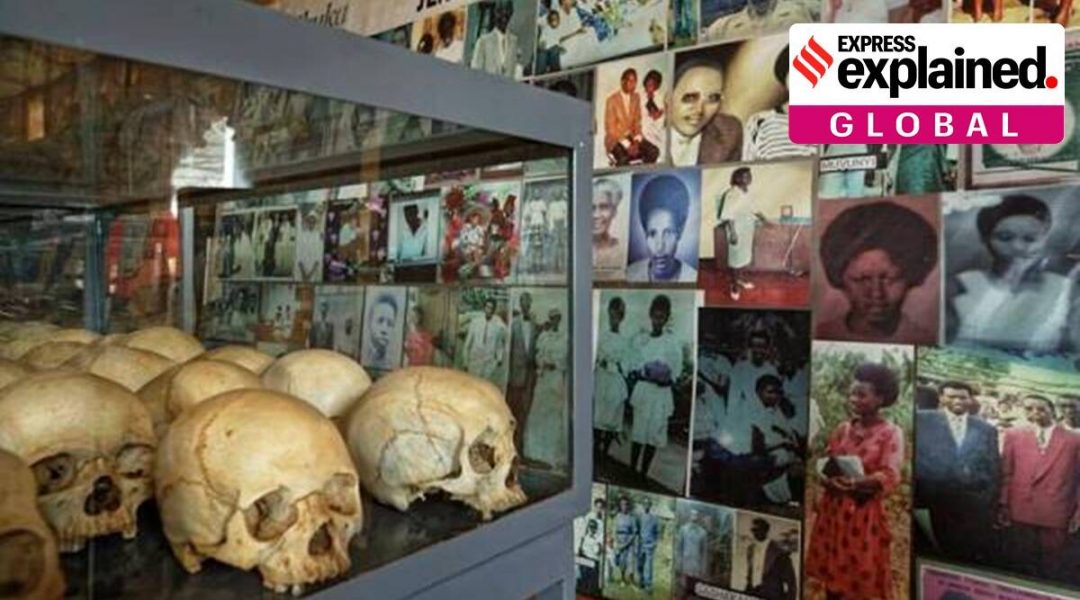

Skulls of some of those who were slaughtered as they sought refuge in the church sit in a glass case next to photographs of some of them, kept as a memorial to the thousands who were killed in and around the Catholic church during the 1994 genocide, inside the church in Ntarama, Rwanda. (AP Photo/Ben Curtis)

French President Emmanuel Macron on Thursday acknowledged his country’s “overwhelming responsibility” in the 1994 Rwandan genocide, but stopped short of a clear public apology.

“France has a role, a story and a political responsibility to Rwanda. She has a duty: to face history head-on and recognise the suffering she has inflicted on the Rwandan people by too long valuing silence over the examination of the truth,” Macron said in a speech at the Kigali Genocide Memorial, where the remains of 2.5 lakh victims of the genocide are interred.

“Standing here today, with humility and respect, by your side, I have come to recognise our responsibilities”.

The remarks were welcomed by Rwandan President Paul Kagame – a fierce critic of France ever since the genocide– who called them “more valuable than an apology” and “an act of tremendous courage”.

France’s partial admission of guilt is seen as part of an effort to mend ties with its former colonies and sphere of influence in Africa,

many still have painful memories of their subjugation, and continue to see French actions with suspicion.

What has Macron said?

In an address that is expected to go a long way in repairing long-fraught relations with Rwanda, Macron went much further than his predecessors in admitting France’s role in the genocide, saying, “Only those who went through that night can perhaps forgive, and in doing so give the gift of forgiveness.”

“France did not understand that, while trying to prevent a regional conflict, or a civil war, it was in fact standing by the side of a genocidal regime,” Macron said, “By doing so, it endorsed an overwhelming responsibility”.

In what appeared to be an explanation for not delivering a clear apology, the French leader said, “A genocide cannot be excused, one lives with it”. He did, however, promised efforts to bring genocide suspects to justice.

The Rwandan genocide

The Rwandan genocide of April-July 1994 was the culmination of long-running ethnic tensions between the minority Tutsi community, who had controlled power since colonial rule by Germany and Belgium, and the majority Hutu. Over the course of 100 days, the tragedy took the lives of over 8 lakh people, estimated to amount up to 20% of Rwanda’s population.

Hutu militias systematically targeted the Tutsi ethnic group, and used the nation’s public broadcaster, Rwanda Radio, for spreading propaganda. Military and political leaders encouraged sexual violence as a means of warfare, leading to around 5 lakh women and children being raped, sexually mutilated or murdered. Some 20 lakh fled the country.

The conflict ended when the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front seized control of the country in July, and its leader Paul Kagame assumed power. Kagame, who has led Rwanda ever since, has been credited for bringing stability and development to the mineral-rich nation, but blamed for cultivating an environment of fear for his political opponents both at home and abroad.

What role did France play during these events?

During the genocide, Western powers including the United States were blamed for their inaction which abetted the atrocities. France, which was then led by Socialist President François Mitterrand, gained notoriety after being accused of acting as a staunch ally of the Hutu-led government that ordered the killings.

In June 1994, France deployed a much-delayed UN-backed military force in southwest Rwanda called Operation Turquoise– which was able to save some people, but was accused of sheltering some of the genocide’s perpetrators. Kagame’s RPF opposed the French mission.

How did France and Rwanda get along after the conflict?

Bilateral relations nosedived after the genocide, as leaders in Rwanda as well as elsewhere in Africa were infuriated by the role of France. Kagame drew his country – whose official language had been French ever since Belgian rule – away from France, and brought it closer to the US, China and the Middle East. Kagame also broke off relations with France at one point.

In 2009, Rwanda also joined the Commonwealth of Nations, despite having no historical relations with the UK. Interestingly, even as Kagame praised Macron’s remarks on Thursday, he did so in English and not French.

In 2010, conservative French President Nicolas Sarkozy became the first head of state to visit Rwanda since the genocide, but relations continued to deteriorate despite Sarkozy admitting to “serious mistakes” and a “form of blindness” by the French government during the blood-soaked turmoil.

What changed under Macron?

Macron has presented himself as part of a new generation that is willing to revisit the painful parts of France’s legacy as a colonial power in Africa and of later supporting ruthless dictators in the post-colonial period.

During his election campaign in 2017, Macron had called the French colonisation of Algeria a “crime against humanity” and the country’s actions “genuinely barbaric”. In March this year, Macron admitted that French soldiers tortured and killed the Algerian lawyer and freedom fighter Ali Boumendjel, whose death in 1957 had been covered up as a suicide.

To counter allegations of paternalism in French-speaking Africa, Macron has also sought to engage with English-speaking countries of the continent. Sure enough, even on his current visit to Africa, Macron is going to English-speaking South Africa immediately after Rwanda.

So, what led to a thaw in France-Rwanda relations?

In March and April this year, two reports came out examining France’s role in the conflict. The first report, which was commissioned by Macron, gave a scathing account of French actions during the genocide, accusing the then-French government of being “blind” to preparations by the Hutu militia, and said that the European power bore “serious and overwhelming” responsibility, according to France24. The report, however, did not find proof of France being complicit in the killings.

The Macron government accepted the findings of the report, marking a game-changer in France-Rwanda relations. Kagame visited France last week, and said that the report enabled the two countries to have “a good relationship”. Before Macron’s reciprocal visit to Rwanda this week, the two sides spoke of a “normalisation” of relations.

What have been the reactions to Macron’s admission?

While Macron did speak of “forgiveness”, some were dismayed by France not delivering a clear apology on the lines of Belgium, whose Prime Minister Guy Verhofstadt in 2000 publicly apologised for failing to prevent the genocide, or the United Nations, whose Secretary-General Kofi Annan did the same in 1999.

Still, Rwandan President Kagame welcomed Macron’s remarks, saying, “His words were something more valuable than an apology. They were the truth”.

Macron’s stopping short of a full apology is being interpreted as an attempt to not rile up conservatives back home in France, who see French actions in Africa over the years as a relatively benign influence. Less than a year remains until the 2021 presidential race, when Macron is expected to face the ultra-right Marine Le Pen, who was also his opponent in the last election.

The French President, however, will face a considerably more formidable challenge walking the tightrope in March next year, barely a month before the polls, when Algeria, a prized former colony, will celebrate 60 years of independence. In January this year, Macron said that there would be “no repentance nor apologies” but “symbolic acts”, yet many are expecting matters to get heated over the polarising topic.