Economy

Arunachal Prades Tea touches the record heights set by Assam tea

A variety of tea grown in Arunachal Pradeshon Wednesday touched the record heights set by Assam tea earlier this month selling for Rs 75000 per kg at the Guwahati Tea Auction Centre (GTAC).

‘Golden Needle‘ tea produced by Donyipolo Tea Estate in Arunachal Pradesh was sold by Contemporary Tea Brokers and was bought by city-based buyer Chattar Singh Narendra Kumar for online tea seller Absolute Tea, GTAC Buyers Association secretary Dinesh Bihani said.

On August 13, Dikom Tea Estate of Assam had sold its Golden Butterfly tea at Rs 75,000 per kg at the GTAC, auction centre official said.

Donyipolo Tea Estate had last year set a record when their tea was sold for Rs 39000 per kg, Bihani said.

“These teas do not draw the real picture of the tea industry. But the industry should appreciate producers who are making top notch teas and are making a name for Indian Tea Industry in the world,” Bihani said.

Arunachal Pradesh recently came up in the tea map of the country for producing speciality tea. These have been appreciated by tea lovers across the world, Bihani said.

“We had bought Donyipolo Golden Needles in the past few years. The response has been superb and we expect a similar response this year,” Kumar said.

The tea was made from the tips of selected clones by skilled artisans, Satyanjoy Hazarika, managing director, tea, of Contemporary Brokers said. PTI

by Dr Catherine Owen: ——-The topic on every internationally minded Chinese person’s lips when in conversation with a Westerner appears to be the US-China trade war. The following text summaries my informal discussions over lunch and during walks, with friends and colleagues in Shanghai, on the reasons behind, and potential consequences of, growing economic tensions between the world’s two largest economies. My interlocutors are researchers and postgraduate students at some of Shanghai’s elite universities, as well as start-up entrepreneurs and employees of major Chinese tech firms. Our discussions highlight a troubling thesis: many worry that this trade war may be a precursor to a greater conflict, driven by US reluctance to cede its hegemonic position to a rising China. Ultimately, the discussions illustrate that the trade war embodies two irreconcilable visions of global economic order.

The topic on every internationally minded Chinese person’s lips when in conversation with a Westerner appears to be the US-China trade war. The following text summaries my informal discussions over lunch and during walks, with friends and colleagues in Shanghai, on the reasons behind, and potential consequences of, growing economic tensions between the world’s two largest economies. My interlocutors are researchers and postgraduate students at some of Shanghai’s elite universities, as well as start-up entrepreneurs and employees of major Chinese tech firms. Our discussions highlight a troubling thesis: many worry that this trade war may be a precursor to a greater conflict, driven by US reluctance to cede its hegemonic position to a rising China. Ultimately, the discussions illustrate that the trade war embodies two irreconcilable visions of global economic order.

Background to the Trade War

The roots of the trade war lie in accusations by the US and other countries of economic malpractice by the Chinese government, in particular, the violation of intellectual property rights and the privileging of Chinese State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) in the domestic market. First, intellectual property theft has allegedly occurred in two ways: through the requirement that foreign companies share their technology when accessing Chinese markets, and through the use of spyware and hackers, both by the Chinese government [1] and by businesses, such as Huawei (though no evidence for this has yet emerged). Second, the Chinese approach to economic management, consisting of state subsidies for SOEs and preferential treatment for SOEs vis-à-vis foreign companies, is seen to violate WTO regulations stipulating a level playing field for international trade. In short, the US is demanding profound structural changes in the way that Beijing manages the Chinese economy – that it ditches, or at least softens, its commitment to a managed economy.

Thus, the Trump administration launched an investigation[2] immediately upon taking office in January 2017, having long been critical of Chinese financial practices. Since March 2018, the Trump administration has applied over $250 billion worth of trade tariffs onto Chinese goods imported into the USA, arguing that the tariffs will make Chinese goods less competitive and encourage consumers to choose products made in America, thereby reducing the US’ large trade deficit with China. Predictably, Beijing responded by applying $110 billion of trade tariffs onto US goods. At the time of writing, the trade war has been paused to allow negotiators to try to reach a deal before the 2nd March deadline when a further $200 billion of US tariffs on Chinese goods are due to come into force. Progress, unfortunately, is slow.

The perceived poster child for these practices is arguably ‘Made in China 2025’[3], China’s strategic plan to move away from its position as the global ‘shop floor’ for cheap manufactured goods, and catch up with high-tech Western companies in the fields of robotics, transport, aerospace, pharmaceuticals, and energy and agricultural equipment. Launched in 2015, the aim is to increase the market share of domestic high tech suppliers to 70% in ten years and ensuring that a specific number of component parts in various products should be produced domestically. Critics argue[4] that in order to achieve these lofty goals, MiC2025 will involve a smorgasbord of economic malpractices, including both intellectual property theft and preferential treatment for Chinese companies. In the wake of this criticism, MiC2025 has mysteriously disappeared from the media limelight in recent months; it is however unlikely that the project has been abandoned.

Obscured in the British media by the omnipresent and all-consuming Brexit coverage, the trade war is an issue with far reaching consequences, not only slowing growth in China, but also in other Asian economies, such as Japan and South Korea, which depend on exports of specialised parts to China that are then used to make technical equipment and mobile phones. Furthermore, the trade war is also impacting the US economy, and the IMF[5] and World Bank[6] have both issued concerns that it could trigger a global recession.

Chinese Views

The Chinese intellectual classes have been following developments very closely. Yet, due to the lack of diversity of viewpoints represented in the Chinese media, several common themes emerged during my discussions. The most prevalent view among my interlocutors, also widely promulgated in the Chinese popular press, is that the West believes that China is rising too fast and has applied a trade war in order to prevent China from becoming a global superpower. The phrase, ‘Thucydides’ Trap’[7], coined by US political scientist Graham Allison to describe the near inevitability of war when a rising power seeks to displace the hegemonic power, is well known.

More than one Chinese linked the discussion to a consideration of why Xi Jinping last year extended his presidency indefinitely. Was it because the defining task of his presidency is to ensure China becomes the new global hegemon and, in order to do this, a war is necessary? Friends pointed to the defining acts of other important Chinese leaders – Mao Zedong’s establishment of the People’s Republic of China, Deng Xiaoping’s reform and opening up of the country – and suggested that Xi believes his historic task is to finally place the Middle Kingdom at the centre of the global order. This is not a prospect that my interlocutors relish; comfortable members of the nascent middle class, they do not want military conflict to threaten new-found stability.

Other, less sensationalist perspectives acknowledge that China has been violating WTO regulations for some time, and that its transparency record is indeed poor. However, they also observe that China is far from alone in failing to adhere to WTO best practice and fall back on the fear of China’s rise thesis to explain why the US is targeting them over other states. Some point to the personal characteristics of Donald Trump, a businessman with a ‘zero-sum’ mentality, who is thought unable to see trade from the ‘win-win’ perspective of the Chinese. A third, much smaller group suggest that the impact of the trade war has been overblown by the Chinese government to mask other failings in the Chinese economy, such as the impossibly high tax rates for small and medium sized businesses, the ageing population, and slowing consumption patterns.

An Ideological Impasse?

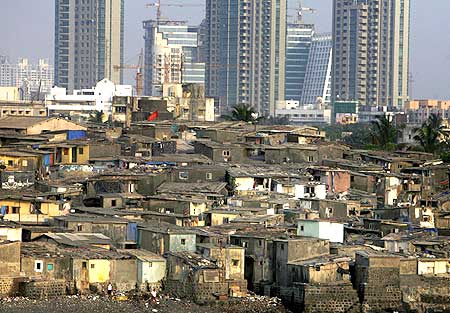

The trade war, in some senses, can be seen as a battle of capitalisms. China’s rise has demonstrated that countries able to control their economies, especially via protectionist measures in particular sectors, are able to achieve remarkable economic performance. Indeed, the ‘China model’ of state capitalism has lifted over 500 million people out of poverty since 1981, reducing the percentage of those living on less than two dollars a day from 88% to 6.5%; meanwhile the poverty rate in the US has remained more or less constant between 11.5 and 15%.[8] This fact rankles the current defenders of global free market capitalism; yet, ironically, in demanding that China opens its economy, the US imposed trade tariffs actually damage the openness of global trade on which this order is founded. While the astonishing growth of China’s middle class is now inevitably levelling off, China’s rise nevertheless poses an existential challenge to the universal applicability of Western-oriented capitalist model. Could this trade war constitute the first sign of the death throes of the liberal economic order?

[1] Chinese Officer Is Extradited to U.S. to Face Charges of Economic Espionage, October 2018, New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/10/us/politics/china-spy-espionage-arrest.html

[2] Section 301 Report into China’s Acts, Policies, and Practices Related to Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, and Innovation, March 2018, Office of the US States Trade Representative https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases/2018/march/section-301-report-chinas-acts

[3] State Council of The People’s Republic of China, http://english.gov.cn/2016special/madeinchina2025/

[4] How ‘Made in China 2025’ became a lightning rod in ‘war over China’s national destiny’, January 2019, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/2182441/how-made-china-2025-became-lightning-rod-war-over-chinas

[5] US trade war would make world ‘poorer and more dangerous’, BBC, October 2018, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-45789669

[6] WTO chief warns of worst crisis in global trade since 1947, BBC, November 2018, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-46395379

[7] Is war between China and the US inevitable?, Ted Talks, September 2018, https://www.ted.com/talks/graham_allison_is_war_between_china_and_the_us_inevitable

[8] Following the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) Statistical Policy Directive 14, the U.S. Census Bureau uses a set of dollar value thresholds that vary by family size and composition to determine who is in poverty see https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/demo/p60-263.pdf

FPC Briefing: The Authoritarian-Populist Wave, Assertive China and a Post-Brexit World Order

by Dr Chris Ogden

Over the last decade, the rise of authoritarian tendencies represents an increasing illiberal wave in international politics. Such a wave is not limited to smaller countries but increasingly typifies the political leadership and underlying nature of the international system’s foremost powers, in the guise of the United States (US), Russia, China and India, who are normalizing authoritarian-populism as a dominant global political phenomenon. In this regard, we must recognise that authoritarianism and democracy are not opposing political systems but are fundamentally inter-related on one continuum, whose characteristics co-exist and significantly influence each other. China is at the vanguard of this phenomenon and provides a clear counterpoint to western liberal democracy. With western democracies heavily reliant upon China’s continued economic growth and facing significant political upheavals and crises, in particular, Brexit, the essence of the liberal world order may soon be on the verge of capitulation to China’s preferred authoritarian basis.

Authoritarian and populist tendencies are escalating in the international system, transforming the nature of domestic and global politics. Permeating the domestic proclivities of countries ranging from Hungary, Poland and Turkey, to Mexico, Brazil and the Philippines, ‘nearly six in ten countries … seriously restrict (their) people’s fundamental freedoms of association, peaceful assembly and expression’. Authoritarian-populism is now also a shared phenomenon among the world’s most influential countries, and the rise of authoritarian tendencies among the great powers characterises an increasing illiberal theme in international politics over the last decade[2].

‘Anti-elitist’, assertive and nationalist-minded leaders all currently lead the world’s great powers – the United States (US), Russia, China and India – with each proactively proclaiming a common nationalistic goal of restoring their countries’ past glories and status. Via their economic, military and diplomatic strength, as well as substantial, growing and evermore vocal populations, it is these four major powers – more than any other countries – that will determine and delineate the foundations of world politics – and of the prevailing world order itself – in the decades to come.

As such, in the US, the populist President Trump openly questions civil liberties, attacks the media, and side-lines and undermines major bureaucratic and legal bodies. In China, President Xi’s repressive government has increased internet surveillance, imprisons human rights activists, and threatens and re-educates religious activists. In Russia, an autocratic President Putin silences liberal opposition groups, restricts free speech, and controls media outlets. And in India, Prime Minister Modi’s Hindu nationalist rule is typified by heightened state censorship, the frequent banning of non-governmental organisations, and increased violence towards minority groups.

A range of key factors critically binds these four leaders together; primarily their highly personalistic leadership styles, their desire for centralized political control, their appeal to mass public audiences, and their sustained intolerance of dissent. Of note too is that even before President Trump gained power, the US was downgraded to the status of a “flawed democracy” in the Economist’s Democracy Index 2016[3]. India holds a similar standing, whilst Russia and China are considered authoritarian. The Index bases its comparison across a range of factors, including the electoral process and pluralism, functioning of government, political participation, political culture and civil liberties, underscoring the commonalities between these countries.

Given the vital role that these great powers perform as the shapers and creators of global institutions – and therefore of accepted behaviours and practices in the international sphere – as they become more authoritarian in nature so too will the dominant world order. Moreover, how they understand, demonstrate and deploy authoritarian-populist traits via their autocratic leaders has the potential to threaten the stability of democratic societies throughout the world, including in Britain and the European Union. Critically, we need to see that authoritarianism and democracy are not opposing and exclusive political systems but that they are fundamentally inter-related on one continuum. In this way, there is no fixed, binary divide between democracies and authoritarian regimes but instead, they are essentially fluid, inter-connected and impermanent entities, whereby democracies can display particular authoritarian inclinations and vice versa.

Chinese-Style Authoritarianism

Through a one-party state dating from 1949, the Chinese Communist Party presently rule with an authoritarian political basis that seeks to inhibit political pluralism, sanction political participation, imprison opponents (including political, ethnic and religious groups, most notably China’s Uighur population), and use state apparatuses to strictly monitor, control and command their population. China’s specific political nature relates to core elements of its specific world vision, in particular a set of desires pertaining to centralized control, territorial restoration and restored recognition, along with the continued impact of Confucian beliefs concerning harmony, peace, hierarchy, respect and benevolence – principally across East Asia. These various factors are informed by particular leadership styles, especially the more assertive and nationalistic Xi Jinping, who in October 2017 pertinently stated that ‘no one political system should be regarded as the only choice and we should not just mechanically copy the political systems of other countries’[4].

China’s authoritarian-populism is deep-seated in nature and is the hallmark of the country’s bureaucratic, legal and security institutions. These elements produce a political basis that critically contrasts to core dynamics integral to the current world order orientated around Western liberalism, as based upon democratic practices, tolerance, the rule of law, and protecting individual (rather than collective) human rights. As China’s stature increases, via the country’s ongoing economic, military and diplomatic rise, its global pre-eminence will allow the country to influence the functioning of the international system and threaten the predominant parameters of the current world order. This will allow for the realisation of Xi’s ‘Chinese Dream’ that ‘is a dream about history, the present and the future’, and inter-connects China’s longstanding values with its ambitions. By enabling a new world order, China’s supremacy in 1) economic, 2) institutional and 3) normative terms will be paramount and echo the country’s specific domestic values, which are deeply historically engrained in the mind-sets of its leaders, thinkers and people.

Economics

With China now possessing the world’s largest economy[5], it is acquiring a system-determining capacity that allows it to cast its own vision of authority, order and control throughout the contemporary international structure. The country’s gradual embrace of liberal economics – often merged with specific Chinese values and characteristics based upon state control and a blurring between public and private ownership – has given it this ability. This has resulted in an economic system defined as being authoritarian-capitalism that diverges from the western liberal economic ideal. In addition, China’s ever-increasing demand for resources, markets and energy has made the world’s composite national and regional economies dependent upon it as a major import and export market, cheap labour provider and fruitful foreign investment destination[6].

Beijing’s wild success in rapidly transforming the economic fortunes of its population, pulling hundreds of millions out of poverty and conducting its international trade in a non-ideological manner, also acts as an inspirational developmental model for countries across Africa and Asia – particularly those with authoritarian regimes. By doing so, China deeply questions the legitimacy of western liberalism’s declaration that economic growth inevitably leads to democracy, and – by presenting a viable alternative to it – shows that such a world order can be usurped and replaced. Beijing’s planned Social Credit System[7], which will come into force in 2020, inter-links educational achievements, financial behaviour and social media activity to produce a transparent and publicly available social score, will extend the Chinese state’s capability to control its people. The technologies central to this control are being exported to other countries[8], and their underlying principles are evident in the west, such as for credit scoring or screening terrorists[9].

Institutions

By binding members together around particular values, practices and understandings, and providing their instigators with a managerial role to govern and regulate international affairs, multilateral regimes aid the creation and maintenance of world orders. Such institutions innately reflect the specific interests, concerns and values of their creators, and are vehicles to disseminate particular visions of the world onto the global stage, as displayed by the western-originated International Monetary Fund, World Bank and United Nations. For most of the latter half of the twentieth century, these institutions encapsulated the US-led vision of a western-orientated world order resting upon an image of international security via liberal free trade and democratic politics.

Underscoring this system-ordering potential, and also its differentiation from existing groupings, China’s beliefs concerning multi-polarity, global governance, human rights, peaceful development and non-intervention are engendering a new form of world order. China’s creation of different regimes, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB, a multilateral development bank founded in 2015), and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO, a Eurasian security organization initially initiated in 1996), encapsulates how its differing attitudes are inculcating a Chinese-led world order. Such an order inherently challenges rival western institutions, and – by extension – the very liberal values upon which they have been crafted, imagined and legitimized.

Normative

Drawing upon how leading great powers not only create world order but also provide leadership, as well as territorial, financial and existential security, a Chinese world order would necessarily change the very conduct and nature of global affairs. China’s domestic identity, history and behaviour pertaining to the acceptance of an autocratic and benevolent form of single- party rule all critically inform this discussion. So too do the wider realization and enactment of the notion of tian xia (“all under heaven”) that seeks to create a China-centred world order that is built upon tenets of hierarchy, paternalism and harmony in its various diplomatic relations across the world.

China’s underlying indigenous authoritarian values, practices and ideas have already altered the structure and workings of the international system, and as China becomes increasingly influential and powerful, they will lead to further significant transformations. Moreover, because authoritarian-populism is increasingly present in the politics of the great powers – as well as in many medium and lower tier countries – it acts as an enabling and legitimizing mechanism for China’s worldview. Such a convergence, accompanied by the weakening of western liberalism, the challenge that China poses to it, and the US’s continued retreat away from leading global affairs, illustrates how China’s authoritarian world order is becoming both feasible and achievable.

Thinking Ahead

The international system is currently experiencing a period of transition as economic, institutional and military power is being amassed by China, which is depleting the relative influence and stature of western countries and their associated values and worldviews. Moreover, Beijing is now able to articulate an alternative vision of world order premised upon different economic, institutional and normative conditions that are becoming increasingly legitimate in the eyes of many world leaders. Growing authoritarian and populist traits across the world – and its dominant great powers – accelerate this trend, as do pressure from domestic populations negatively affected by globalization, increased migration and growing economic disparities.

To effectively counteract the risk posed to their country by the authoritarian-populist wave, leaders in the UK – particularly in the context of Brexit – must remain aware that political systems are inter-connected and evolutionary in nature, and that such systems are all highly susceptible to:

- Shock: Periods of tumult – in the form of a profound economic shock, recession or depression – will only serve to further accentuate and speed up a country’s assimilation to the authoritarian-populist wave. In such an atmosphere, nationalist tendencies will rise as domestic pressures and international uncertainties increase, especially in countries experiencing a deep identity crisis, such as the UK post-Brexit;

- Slippage: In order to prevent them from being replaced by other worldviews, national values – and thus values underpinning particular world orders – require regular maintenance. Populations need to be actively (and regularly) informed concerning their rights, and how such rights were originally won, in order to better sustain the liberal world order. Without such a basis, citizens will be evermore vulnerable to alternative narratives; &

- Isolation: countries separated from dominant economic and political groupings are more exposed to the core factors personifying the authoritarian-populist wave. This means not only nationalist forces – and more extreme political beliefs – but also alternative sources of financial and trade security, which China (and also the US) may be willing to provide but only subject to a tacit acceptance of its preferred worldview.

[1] Quoted in People Power Under Attack 2018 (Monitor Civicus), https://monitor.civicus.org/PeoplePowerUnderAttack2018/

[2] Economist, Democracy Index 2016: Revenge of the “Deplorables” (London: Economist Intelligence Unit), http://www.transparency.org.nz/docs/2017/Democracy_Index_2016.pdf; Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2017 – Populists and Autocrats: The Dual Threat to Global Democracy(Washington DC: Freedom House), https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2017; Polity IV, Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions 1800-2013(Vienna, VA: Center for Systemic Peace), 2014, http://www.systemicpeace.org/polity/polity4x.htm

[3] Economist, Democracy Index 2016: Revenge of the “Deplorables” (London: Economist Intelligence Unit). Accessible at http://www.transparency.org.nz/docs/2017/Democracy_Index_2016.pdf

[4] Quoted in Tom Phillips ‘Xi Jinping Heralds “New Era” Of Chinese Power at Communist Party Congress’, The Guardian, October 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/18/xi-jinping-speech-new-era-chinese-power-party-congress

[5] See ‘Country Comparisons – GDP (Purchasing Price Parity)’, CIA World Factbook, 2017,https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/208rank.html#CH

[6] See ‘Foreign Direct Investment’, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), 2018, http://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/ReportFolders/reportFolders.aspx

[7] Celia, Hatton, ‘China “Social Credit”: Beijing Sets Up a Huge System’, BBC News, October 2015. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-34592186

[8] Rui Hou, ‘The Booming Industry of Chinese State Internet Control’, openDemocracy, November 2018, https://www.opendemocracy.net/rui-hou/booming-industry-of-chinese-state-internet-control

[9] Jimmy Tidey, ‘What China Can Teach the West About Digital Democracy’, openDemocracy, October 2017, https://www.opendemocracy.net/digitaliberties/jimmy-tidey/what-china-can-teach-west-about-digital-democracy

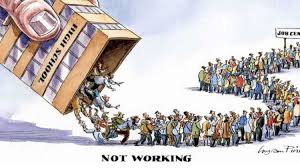

The Centre has effectively sounded the death knell for a quarterly employment surveyBy Basant Kumar Mohanty in New Delhi

Finance minister Arun Jaitley had on Tuesday called more than 100 academics “purported economists” and “compulsive contrarians” for issuing an appeal to restore the credibility of economic statistics and described as “preposterous” suggestions of job losses in the country.

Less than 24 hours later, it emerged how the Narendra Modi government was frittering away a golden chance to prove the “compulsive contrarians” and doubters wrong.

The Centre has effectively sounded the death knell for a quarterly employment survey by not clearing the air on its fate in spite of a funding deadline lurking round the corner.

An expert committee, appointed to look into whether it has lost its relevance, had recommended that the survey be discontinued. The quarterly survey was instituted in 2008 during the global downturn, covering establishments engaging over 10 workers in sectors such as manufacturing, construction, trade, transport, IT/BPO, education and health.

Curiously, the committee to review the relevance of the survey was set up in June 2018 after the figures showed that new jobs had remained below 2 lakh in all quarters since July 2016 and the growth was either negative or flat in manufacturing and construction.

In January this year, the committee headed by former chief statistician T.C.A. Anant recommended discontinuation of the quarterly survey as it felt that the “wealth of information” from the database of the Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation (whose figures differed with those of the quarterly survey) “can be used more rigorously….”

However, by then, jobs had become a hot-button political issue and unpalatable questions were being asked about Prime Minister Modi’s pre-election promise to create 2 crore jobs every year.

Since then, a perceived suppression of indigestible statistics and periodical revisions have landed the official statistical machinery in controversies. Against this backdrop and with elections fast approaching, the government appears to have developed cold feet in taking a clear stand on the fate of the quarterly survey.

Concern had begun to grow in the Labour Bureau, a labour ministry wing that conducts the quarterly survey, because the request for funds to carry out the exercise has to be placed by the last week of March.

Unsure whether the survey will survive or not, the Labour Bureau had written to the Union labour ministry two months ago seeking a clarification.

But the labour ministry has not yet responded, sources said. The dithering stands in sharp contrast to the finance minister’s swift and acerbic response in less than five days to the appeal by 108 economists and social scientists to restore integrity to official data.

However, the Labour Bureau has sent a separate proposal for funds for implementing the newly started area frame survey, which gathers job data in informal units employing less than 10 workers in the eight sectors. The ministry is currently processing the proposal for funding for the new survey.

The Labour Bureau spends around Rs 10 crore every year on the quarterly survey. “The service of the surveyors engaged in the quarterly employment survey will end this month. The survey may stop completely from next month,” an official said.

Sources suggested that the government was not averse to dumping the old survey but it may not take any decision until the elections are over.

Not everyone agrees with the recommendation of the committee to scrap the quarterly survey. Santosh Mehrotra, chairperson of the Centre for Informal Sector and Labour Studies in Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), said the data sets from the quarterly employment survey and the EPFO were not comparable.

“The quarterly survey covered both organised and un-organised sectors. The EPFO covers only the organised sector,” Mehrotra said.

Raghuram Rajan says global economists creating own India index after govt’s tinkering with macro indicators

India’s tinkering with lead economic indicators and suppression of discomforting economic data is prompting global economists to plan an independent index for India, former RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan told India Today TV’s Rajdeep Sardesai and Rajeev Dubey.

“There is a whole lot of noise around our statistics to the extent that investors are starting to get worried and people are talking about a Li Keqiang index for India,” says Rajan.

The Li Keqiang Index was created by The Economist and named after head of China’s Liaoning province who allegedly said he did not trust government statistics and maintained his own index of broad industrial indicators that couldn’t be easily fudged such as electricity consumption and railway volume.

India has restructured the GDP methodology and, of late, withheld discomforting employment data prepared by NSSO which suggested unemployment is at a 4-decade high. India also held back FDI data inexplicably.

Earlier this month, 108 economists had issued a statement objecting to the tinkering with India’s economic indicators. “The national and global reputation of India’s statistical bodies is at stake. More than that, statistical integrity is crucial for generating data that would feed into economic policy-making and that would make for honest and democratic public discourse,” the economists said in a statement.

Their move was later countered by 131 chartered accountants who endorsed the government’s statistics and called the economists’ intervention “baseless allegations with political motivations”.

A US State Department memo exposed by WikiLeaks said, Li Keqiang who was then the People’s Party Committee Secretary for Liaoning, told US ambassador that he did not trust Liaoning’s GDP numbers. Hence, he created his index of three leading indicators: Rail cargo volume, electricity consumption and credit issued by banks.

Investment bank Haitong Securities also used the term ‘Keqiang index’ in its index to indicate the deceleration in China’s economy since 2013.

“Some people are developing a Li Kequiang Index for India because they are no longer paying attention to the GDP numbers. Our GDP numbers are not being trusted by international investors which is why we need some outside opinion, a committee of experts, may not be all from outside the country but who can reliably pronounce on the quality of our statistical structure,” says Rajan.

Incidentally, right after the restructuring of India’s GDP methodology, Mumbai-based broking firm Ambit Capital had created its own Keqiang Index. Ambit’s Keqiang Index captured power consumption, air cargo, vehicles sales and capital goods imports.

The world happiness report for 2019 has put Finland on the top spot on the most happiest country for the second consecutive year. According to reports, Finland is the happiest country amongst 156 nations surveyed by the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network. India has dropped down seven spots in the happiness rankings as compared to its 2018 ranking. Media quoted the report saying with the increase in population, the overall happiness has dropped worldwide.

In 2018, India was placed on 133 position, but this year its ranking went down to 140. In 2015, India was on 117 spot, in 2016 it was ranked on 118 spot. The position went up to 122 in 2017, according to reports.

Various factors that determine the happiness levels of a country include life expectancy, social support, income, freedom, trust, health and generosity, amongst others.

The immediate neighbours of India including Pakistan, Bhutan, Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka are way ahead in the happiness rankings. In this report, Pakistan stands at 67th rank, China at 93, Bhutan at 95, Nepal at 100, Bangladesh at 125 and Sri Lanka at 130, leaving India way behind.

Here’s a list of Top 10 happiest countries of the world:

The World Happiness Report 2019 has disclosed the list of happiest and unhappiest countries worldwide. Finland, for the second consecutive year, has topped this list. It is followed by Denmark, Norway, Iceland, Netherlands, Switzerland, Sweden, New Zealand, Canada and Austria.

Here’s a list of Top 10 unhappiest countries of the world:

South Sudan has topped the list of the unhappiest countries of the world. It is followed by Central African Republic at 2nd spot, Afghanistan at 3rd and Tanzania, Rwanda, Yemen, Malawi, Syria, Botswana and Haiti, respectively at the next spots.

The World Happiness Report is a landmark survey of the state of global happiness. It ranks the citizens of 156 countries based on how happy they perceive themselves to be. The World Happiness Report 2019 focuses on happiness and the community.

In open letter, 108 economists say Indian statistics were ‘being influenced and controlled by political considerations’.9 hours ago

A group of more than 100 experts have sounded a pre-election alarm over Indian economic data, accusing Prime Minister Narendra Modi‘s government of tweaking or burying unwelcoming numbers.

Modi is vulnerable over his economic record in the polls starting on April 11, in particular over a failureto meet promises to create enough jobs for the million Indians entering the labour market each month.

The warning comes after India‘s central bank chief quit in December following a spat over alleged government interference. His successor, a Modi ally, oversaw an economy-boosting cut in interest rates last month in his first monetary policy meeting.READ MORE

India’s economy slows before national election

The 108 economists and social scientists said in an open letter on Friday that Indian statistics were “under a cloud for being influenced and indeed even controlled by political considerations”.

“[Any] statistics that cast an iota of doubt on the achievement of the government seem to get revised or suppressed on the basis of some questionable ideology,” they said.

The opposition Congress party of Rahul Gandhi, who has called Modi’s record on employment a “national disaster”, jumped on the letter.

“How much more can this govt. embarrass us on a global level?,” the party said on its official Twitter account.

Economists in fellow emerging Asian giant China and abroad have long suspected that data there is also massaged, often noting that full-year gross domestic product hits Beijing’s pre-set targets with suspicious regularity.

‘Highest in a decade!’

![PM Modi is vulnerable over his economic record in the national election starting on April 11 [Jitendra Prakash/Reuters]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/imagecache/mbdxxlarge/mritems/Images/2019/3/7/724f2accf2e742b89e3482cc62331608_18.jpg)

In 2015, the Indian Central Statistics Office (CSO) revised economic output numbers for past years, changing the base year and showing significantly faster and questionable growth rates.

The letter also questioned a revised growth rate of 8.2 percent in 2016-17, “the highest in a decade”, that “seems to be at variance with the evidence marshalled by many economists”.READ MORE

India announces general election from April 11, results on May 23

That raised particular suspicion since it was when “demonetisation” – one of Modi’s biggest and most derided economic policies when 86 percent of banknotes were withdrawn – hit businesses hard.

This was followed in 2017 by the tardy nationwide rollout of Goods and Services Tax(GST), which has been praised by experts but has had considerable teething problems.

The letter also noted that a major and overdue survey on employment has still not been released. Two senior statistics officials have resigned in protest against the delay.

Press reports have said the study, the first of its kind since 2011-12, showed unemployment was at its highest since the 1970s. The government says it has not been finalised.

“The national and global reputation of India’s statistical bodies is at stake. More than that, statistical integrity is crucial for generating data that would feed into economic policy-making and that would make for honest and democratic political discourse,” the report said.

Signatories included Sripad Motiram from the University of Massachusetts Boston, Paul Niehaus of the University of California San Diego and Abhijit Banerjee of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

“Quality of data has deteriorated and governmental interference has created an atmosphere where we don’t have objective assessment of India’s economic growth,” Ashutosh Datar, an independent economist, told AFP news agency. “The government’s interference has created a huge problem.”

The government was yet to comment on the letter.

Al Jazeera

by Rajesh Rai

Phuentsholing: Bhutanese exporting cardamoms to India are desperate for a government intervention.

After the Goods and Services Tax (GST) impose since July 1 last year, Indian customs offices have implemented the computerised system called ICEGATE in Indian towns that share a border with Bhutan and are significant trade links.

The ICEGATE system asks exporters clearance certificates from Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) and Plant Quarantine Services of India (PQSI). FSSAI has been managed but the quarantine clearance has not been obtained so far.

PQSI does not issue this clearance for Bhutan and it also does not recognise Bhutan Agriculture and Food Regulatory (BAFRA) certification the exporters get in Bhutan.

The issue has also been raised in several meetings in Phuentsholing in the past but there have been no measures taken.

Initially, the system was not installed in Samtse and Bhutanese exporters took their produce to the place to export it to India despite the implication of transportation costs. All the border areas now have the system.

Without quarantine clearance, Bhutanese cardamom demand has decreased, thus, affecting the price.

Cardamom fetched prices between Nu 700 and Nu 800 per kilo (kg) in 2017 but today the price has plummeted to Nu 450 to Nu 480.

Exporters say cardamom exported to India today is also done “informally” and it has affected the price further.

Although exporters still managed to export “informally,” a manager with Bhutan Export Business Line (BEBL), Yeshey Wangchuk, in Phuentsholing said their buyers in Siliguri faced problems related to GST.

“Our buyers have to show where the cardamoms are being imported from,” he said. “If we cannot export it legally the rates would further dip.”

When cardamom cannot be exported legally, farmers are at the losing end, as the prices keep on dropping due to low demand, Yeshey Wangchuk said. “The situation is same with cardamom traders in Gelephu.”

After the GST regime was commenced, the customs office across the border in Jaigoan has stopped recognising the certification from BAFRA and asked the exporters to get certification for every single consignment from Kolkata, India.

Meanwhile, the Indian agriculture ministry had notified in 2003 list of entry points for import of plants and plant materials under Schedule-I and this does not include any of the exit points from Bhutan to India. Jaigaon for Phuentsholing, Chamurchi for Samtse, Daranga for Samdrupjongkhar and Dadgari for Gelephu are not listed and recognised under PQSI.

Schedule-VII of the same notification also states that the large cardamom is in the list of plant and plant materials under which imports are permissible on the basis of phytosanitary certificate issued by the country. But BAFRA certificate is not recognised by ICEGATE.

Joint managing director of RSA private limited in Phuentsholing, who is also a cardamom exporter, Singye Namgyel Dorji, said they had written about the situation to the ministry of economic affairs.

“The biggest problem today is that we cannot legally export to India,” he said, adding that the buyers don’t want to buy from Bhutan because Bhutanese cannot produce the quarantine certificate that is used to pass the GST system.

Considering the problem of not having the document, buyers will buy only if the price was really low, Singye Namgyel Dorji said. “In the long run, it would be better to have BAFRA link with PQSI so that its certificate would be recognised.”

For a short-term measure, the RSA joint managing director said that those Indo-Bhutan towns should be added in the list of the 2003 notification. “Jaigaon, Chamurchi, Daranga and Dadgari should be included in the list, after which the PQSI can do the quarantine.”

RSA had proposed this to the interim government this September.

Earlier this month, some exporters also had told Kuensel that it was the middlemen who work for some Bhutanese exporters that syndicated and manipulated the price.

Singye Namgyel Dorji, however, said it is not true.

“Each farmer cannot tie up with exporters,” he said, explaining farmers need to go through middlemen who buy and aggregate the cardamom in mass. “They then give us the cardamom.”

Since the middlemen, who are individuals from across the border, cannot export owing to several documentations, RSA buys from them.

Rajesh Rai | Phuentsholing