- Google has a new paper in Nature that shows the results of a quantum computing experiment.

- One practical application of the technology could be a decade away, Google CEO Sundar Pichai says.

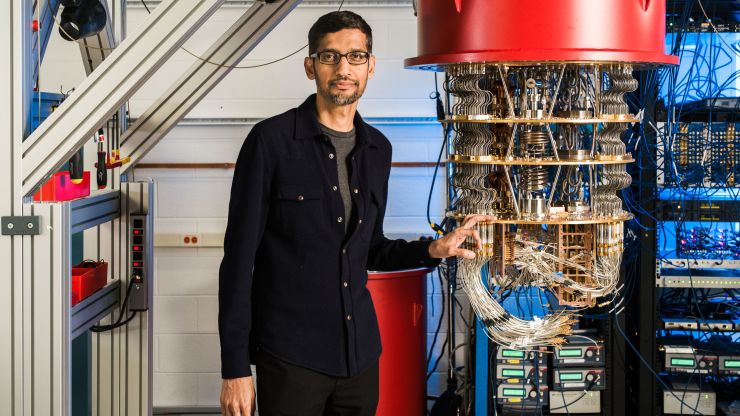

Image Google CEO Sundar Pichai stands with a quantum computer a Google laboratory in Santa Barbara, CaliforniaGoogle

Alphabet subsidiary Google on Wednesday touted a breakthrough in computing research that’s documented in the latest issue of the journal Nature. The paper was actually released online by accident last month by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, which contributed on the research alongside Google, and was quickly removed. Now the full paper is live.

There’s just one problem: IBM thinks Google has overstated its achievement.

The controversy is the latest example of major technology companies trying to one-up each other in quantum computing, a futuristic realm with no clear winner yet. Microsoft and Intel have also been working actively in the area.

Quantum computing is utterly unlike today’s computing. Our existing PCs and mobile devices express information that ultimately gets boiled down to ones and zeros. Quantum computers work in quantum bits, or qubits, which is more nuanced — information can be a one and a zero at the same time.

This technology has promise. It could come in handy to solve problems that modern computers aren’t so good at. It could improve the computing of artificial intelligence models, and it could help with materials science and chemistry work. It could even be used to break encryption one day, and Google is aware of that possibility.

Google’s Nature paper talks about an experiment that researchers conducted with a custom 54-qubit processor called Sycamore. The goal for Google was attaining quantum supremacy — essentially doing something with a quantum computer that would take an impractically long time with normal computers. Google has been focused on the challenge of quantum supremacy — a concept that dates to 2012 — for some time.

“Our Sycamore processor takes about 200 seconds to sample one instance of a quantum circuit a million times — our benchmarks currently indicate that the equivalent task for a state-of-the-art classical supercomputer would take approximately 10,000 years,” the researchers wrote in the paper.

“This dramatic increase in speed compared to all known classical algorithms is an experimental realization of quantum supremacy for this specific computational task, heralding a much-anticipated computing paradigm.”

Google tapped its own computing infrastructure as well as Summit, currently the world’s most powerful supercomputer, to simulate the quantum work and then extrapolate.

IBM took issue with the 10,000-year calculation.

“We argue that an ideal simulation of the same task can be performed on a classical system in 2.5 days and with far greater fidelity,” IBM’s Edwin Pednault, John Gunnels and Jay Gambetta wrote in a blog post. They said quantum supremacy in the strictest terms had not in fact been accomplished.

Applications in drug discovery, climate change

Leaving aside IBM’s skepticism about how long it would take a classical computer to do what Google’s chip did, the question now becomes what Google, IBM and other companies will eventually be able to do with their quantum systems.

“We are only one creative algorithm away from valuable near-term applications,” the researchers wrote in the Nature paper.

Google CEO Sundar Pichai was asked about this in an interview with MIT Technology Review. The answer suggests that the company at least has some clues about the possibilities.

“The real excitement about quantum is that the universe fundamentally works in a quantum way, so you will be able to understand nature better. It’s early days, but where quantum mechanics shines is the ability to simulate molecules, molecular processes, and I think that is where it will be the strongest. Drug discovery is a great example. Or fertilizers — the Haber process produces 2% of carbon [emissions] in the world. In nature the same process gets done more efficiently.”

Evolving the Haber process, he said, could be a decade away.

The IBMers also recognized that much more work lies ahead.

“For quantum to positively impact society, the task ahead is to continue to build and make widely accessible ever more powerful programmable quantum computing systems that can implement, reproducibly and reliably, a broad array of quantum demonstrations, algorithms and programs. This is the only path forward for practical solutions to be realized in quantum computers,” they wrote.