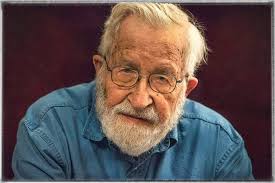

Noam Chomsky shows solidarity with NE’s indigenous people over CAA. Along with Noam Chomsky, James Scott and Survival International also extended support to the concerns of Northeast people over Citizenship (Amendment) Act, informs Richard Kamei, He is a PhD candidate at Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai.

The passage of Citizenship (Amendment) Bill (CAB) encountered vehement protests from Assam, Tripura, Meghalaya and other Northeast Indian states. Despite opposition at Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha, the President of India gave his assent to it and CAB became an Act — Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA). This spiralled into a spontaneous protest across the country with violent incidents against students and protesters starting off at Assam, Shillong (Meghalaya), Jamia Millia Islamia and other parts of New Delhi, Uttar Pradesh and other states. Internet ban was implemented in various places including Assam, Tripura, then in Meghalaya, and later in parts of Uttar Pradesh.

CAA goes against the values of secularism, equality and democracy, and rights of indigenous people. CAA aims to grant citizenship to persecuted minorities from three neighbouring countries, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Afghanistan on the basis of religion, excluding Muslims.

In the case of Northeast India, the opposition is on the grounds that foreigners irrespective of their religions must not be settled in Northeast region. They fear that it might further change the demography of the region and challenge its diverse ethnicities and identities, culture, custom, and the question of lands. Assam began the protest early on in the year 2016, it then spread to neighbouring states of Northeast India. The region was simmered with intense protests in early 2019; facing the heat, Citizenship Amendment Bill (CAB) lapsed in Parliament early last year.

However, the BJP promised to reintroduce CAB through its election manifesto. They campaigned in Northeast with the help of local ruling class by assuring people that they will not be affected and their concerns will be taken care of. They went on to win majority of the seats in Northeast region. As promised, CAB got introduced and passed in both Houses of Parliament and became an Act with the assent of the President.

To facilitate its passage, Inner Line Permit (ILP) was re-introduced in Manipur, and in Dimapur district of Nagaland. The Centre also assured that areas covered by Sixth Schedule will not come under CAA. The assurances and exemptions for Northeast states still leave out major parts of Assam and Tripura where people anticipate that they will be affected by CAA. It is on these that all the Northeast states continue to protest against CAA as they see it to be going against the rights and interests of indigenous people. Professor Noam Chomsky and few other prominent figures were being reached out through an email at this Richard Kamei’s personal capacity. They were informed of the situations of indigenous people of Northeast India and sought their solidarity and support for indigenous people of Northeast India who have been opposing CAB and later CAA through protest, since 2016. A brief history of colonial and settler colonialism in Northeast and CAA implications was written on informing the personalities. The Northeastern part of India is a land of indigenous people numbering hundreds of tribes with their distinct languages, cultures and customs, and identity. The British colonial time is marked with the introduction of settler colonialism into the Northeast region changing its demography, the state of Tripura, for instance, is tremendously affected by it. Tripura, a tribal state, experienced a reduction of tribal population from 87.07% in the year 1881 to 31.78 % of its total population in the year 2011 as per Population history of Tripura recorded in tripura.org.in website. The existence of Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) in large parts of northeast was also being pointed out, in the time when Article 14 of Indian Constitution gained prominence in the minds of people.

They were being informed that these bases made indigenous people in northeast India despite having protective mechanisms like Inner Line Permit (ILP) and autonomous units, fear about losing their identity, culture, and custom, and lands with another wave of settler colonialism through CAA by settling foreigners in the lands of Indigenous peoples. The protest in Assam witnessed the death of five persons, several injured, detained and arrested, and internet blockade for close to 10 days.

Prof Chomsky took time to read and responded within two days. He shared the message to remind indigenous people of Northeast, and people in general opposing CAA, that his support and solidarity is with them: “I have been following these shocking and dangerous developments with deep concern. The Citizenship (Amendment) Act poses intolerable threats to indigenous people, along with many others, and should be strongly condemned by international opinion, which should also support the resistance to the attacks on secular democracy and fundamental human rights being carried out by the Modi administration.”

Professor Scott and Survival International, a human rights organisation that campaigns for the rights of indigenous and/or tribal people and uncontacted peoples, also extended their support and solidarity for the indigenous people of Northeast. They were also being informed about the pending Naga peace talks where the search for its solution continues.

Indigenous people and their struggles more often than not find themselves in a different direction which resides outside of political correctness on the basis of ideological spectrum. Turning towards themselves and devising at their own volition in protecting, preserving and practicing their cultures and customs, traditions and importance of land, has been a marker of indigenous people. The Inner Line Regulation of 1873, as explained by AS Shimray in his book, Let Freedom Ring: The Story of Naga Nationalism, is rooted in the backdrop of flourishing tea plantation where the planters intruded into the lands of the Nagas by trespassing the borders. Land remains inseparable from the identity of indigenous people.

These features encompassing them become more important for assertion as per their past experiences of colonialism and racism, and the vulnerability and threat they face today from the same oppressive forces. It will be unwise to superimpose “borderless imagination” into indigenous people for they are yet to be on equal footing with people from mainstream societies.

On the question of immigrants, the state has a big role to address it in humane ways by prioritising indigenous peoples rights and ensuring at the same time that foreigners/persecuted minorities from neighbouring country get a fair support to lead a dignified life by settling them in other parts of the country which does not come under tribal lands. Last but not the least, taking into accounts of solidarity message from prominent figures like Chomsky and his ilk is not about seeking validation. For indigenous people where survival is their immediate concern, ‘visibility’ is important to carry forward their cause and struggle. It is in this that voice of renowned figure is important to ‘amplify’ tribal peoples’ voices and their struggles.(Richard Kamei can be reached at jenpuna@gmail.com. )