Billy, Muenoor and their child

An oil barrel discovered at the bottom of a reservoir in a nature reserve in Thailand in April 2019 has cast a light on a story some would rather stayed hidden. It is a tale of powerful men and the lengths they will allegedly go to keep their crimes covered up. But it is also the story of one woman’s determination to get justice for the man she loved and the community he was fighting for.

An oil barrel discovered at the bottom of a reservoir in a nature reserve in Thailand in April 2019 has cast a light on a story some would rather stayed hidden. It is a tale of powerful men and the lengths they will allegedly go to keep their crimes covered up. But it is also the story of one woman’s determination to get justice for the man she loved and the community he was fighting for.

Pinnapa “Muenoor” Prueksapan remembers the words that her husband told her back in 2014 as if it happened yesterday.

“He told me: ‘The people involved in this aren’t happy with me. They say that if they find me they’ll kill me. If I do disappear, don’t come looking for me. Don’t wonder where I’ve gone. They’ll probably have killed me’.

“So I said to him: ‘If you know you’re in danger like this, why can’t you stop helping your grandfather and the village?’.

“And he said to me: ‘When you’re doing the right thing, you have to keep fighting, even if it means you may lose your life.’.

“And after he said that, I couldn’t ask him to stop,” she recalls.

When Porlajee “Billy” Rakchongcharoen left for work on 15 April that same year, Muenoor didn’t ask any questions. He left just like any other day, grabbing the overnight bag his wife packed for him and walking out the door without saying goodbye.

He told Muenoor that he was going to meet with people in his role as a locally elected official – but that wasn’t the whole truth. In fact, Billy had gone to meet his grandfather and members of his village to collect evidence to take to lawyers in Bangkok – evidence he hoped would prove once and for all local authorities in this remote part of southern Thailand were illegally evicting indigenous communities.

Three days later, Muenoor got a phone call from Billy’s brother asking if he had arrived home safely. But he still wasn’t home. Suddenly she remembered Billy’s words.

Perhaps that phone call would never had happened had it not been for another tragedy three years earlier.

Billy came from a forest on the Thai-Myanmar border

In July 2011, three military helicopters crashed in a remote part of Kaeng Krachan National Park, near Thailand’s southern border with Myanmar. They went down one after the other in a series of accidents blamed on bad weather.

The tragedy was further compounded by the fact the last two helicopters had been sent to collect the remains of the first.

Seventeen people lost their lives in the three accidents: 16 soldiers and one member of Bangkok’s press.

The crashes drew the attention of the country’s media. Soon journalists from all over Thailand were descending on the area, which meant, for the first time, all eyes were focused on this quiet, rural region – and the dark secrets it hid.

In the end, a tip-off led the journalists to a remote location, far into the dense green jungle of the country’s biggest national park, and to the very secret the soldiers had seemingly died trying to protect.

Because there, deep in the forest, were the charred remains of a village.

The village had once been home to a small indigenous community, made up of about 100 families from the Karen minority. They were farmers, living a simple life, in balance with their surroundings.

It was where Billy had grown up with his grandfather, Karen spiritual leader Ko-ee Mimee.

Their existence, in some ways, sounded idyllic. But the 352,000 Karen people who live in Thailand are seen as outsiders. The majority of the world’s five million Karen people live in neighbouring Myanmar.

But decades of persecution and a long-running civil war with the government in Myanmar have forced thousands of Karen civilians to cross the border, where the Thai authorities have labelled them a foreign threat, said to be associated with drug smuggling and militant insurgencies.

And that is apparently why locals say national park rangers turned up, evacuated the village and burnt everything to the ground weeks before the doomed helicopter flights.

The military helicopter is understood to have been on its way to the village to ensure it had been completely and utterly destroyed.

Park rangers arrived in May 2011, villagers say

Billy wasn’t there the night the park rangers arrived in 2011. He had married Muenoor and moved away to a village nearer her family.

But his grandfather, a spiritual leader and a well-respected member of the village, was at home, and allowed the rangers to stay the night in his hut.

“On that day, there were three helicopters flying above the village,” a Karen man, who wishes to remain anonymous, told the BBC.

“That first day there were 15 park rangers. They went into Billy’s grandfather’s house. They spoke to him and asked to stay for the night.”

Image copyright HANDOUT A hut begins to burn

Image caption The village was evacuated, and the rangers set light to the homes

Ko-ee Mimee had no idea what was about to happen.

“The park rangers didn’t say or do anything that felt threatening, except for the fact they came with guns. The following day, at 9am, the helicopters returned. The village chief told Billy’s grandfather to pack his clothes and walk with the park rangers to the helicopters,” the Karen man recalls.

Even when the villagers were told to get into the helicopters, there was no panicking: they still didn’t understand what was happening.

It was only as they rose up above the trees that the enormity of what was taking place finally became clear.

“As we took off I started to see smoke and I could hear the crackling of the wood from the fire,” the villager tells the BBC. “When the helicopter was high above the village I looked down and saw my whole house in flames.

“Everything inside Billy’s grandfather’s house was burned. All he had was one bag with his hat and a shirt inside. The rest of the villagers weren’t able to bring any of their possessions.

“Everything we had ever owned was burned down along with our homes.”

The farmer who fought back

Chaiwat Limlikidacsorn, then the national park chief, would later tell journalists the families were invaders, and that the village was used as a transit point for Karen drug smugglers coming over the border from Myanmar.

Under Thai law, he would argue, permanent structures could not be built inside protected national parks, and that year Chaiwat’s team of rangers were applying for Kaeng Krachan to become a Unesco World Heritage site.

Billy’s community denied the allegations. They said military maps dating from 1912 even showed their village had existed in the same location for at least a hundred years, and long before the forest became a national park in 1981.

“The way we lived and farmed was in harmony with the forest,” Abisit “Jawree” Charoensuk, a local Karen from the village, tells the BBC. “We Karens respect nature as our God. We worship a water God, a forest God and every living thing in the forest. Our farming technique is environmentally friendly. And we grow things we can consume all year round.

“We catch fish in the river, we catch small animals in the forest and we grow rotation crops. We grow rice to sell and the women weave clothes to sell.”

Achieving the impossible: Thai cave rescue a year on

The sacred water that makes a king

The princess and Thailand’s political games

But after the village was burned, when park authorities moved the community to the outskirts of Kaeng Krachan, things were very different.

“There is no rice for us to harvest because there is no land for us to grow rice on. The land they moved us onto is all rock,” Billy told journalists in 2011. “Since we cannot make a living, we don’t know how to survive. Some of us don’t have Thai citizenship so we can’t look for jobs in the city.

“Many are afraid if they leave the area they’ll be arrested by the police. We can’t make a living down here; we need to go back to where we were.”

The destruction of his village was a turning point for Billy, transforming the young farmer into a human rights activist. He and his grandfather got in contact with lawyers in the capital, Bangkok, some two and a half hours drive away.

A map showing the national park

But it was the helicopter crash which finally gave their plight the attention it needed.

Billy became more and more passionate about getting justice. He organised seminars about Karen community rights, and travelled the country explaining what had happened to his village. He spearheaded attempts to sue the park rangers for compensation.

“Billy acted as an assistant to the lawyer representing the villagers,” Muenoor explains. “He collected evidence for them, spoke to the villagers and found out what happened and what exactly they lost. He took his grandfather to the administrative court so he could sue the national park rangers who burned down their village.”

The disappearance

The last time Billy was seen alive, he was being arrested for taking wild honey out of the forest.

The arrest itself was not unusual: it is illegal to take anything from the forest, but most people pay a fine and are let go.

But Billy had more than just wild honey on him that day. He also had the evidence from the Karen villagers and his grandfather – the same documents he hoped to use in court to sue the park rangers.

When Muenoor tried to report her husband’s disappearance to local police, she says they dismissed her concerns. But she knew in her heart what had happened.

“I thought he was dead because if he was still alive or in hiding he would have found a way to contact me or his family because that’s what he was like – he was a smart guy. He would have found a way to contact me that first day he went missing.”

Billy had been, as the saying goes in Thailand, “carried away”. Human rights groups say thousands of activists have disappeared like this over the decades, although the United Nations puts the number at just 82. Many families are too afraid to go to the police to report their loved ones are missing.

Muenoor, however, was not scared. In the months and years that followed, with the help of lawyers in Bangkok, she launched repeated requests for a judicial investigation into Billy’s unlawful detention.

But time and time again they were rejected on the grounds of a lack of evidence – even though police couldn’t find any record of Billy’s release from custody.

Muenoor was forced to dedicate herself to finding out what happened to her husband

And although traces of human blood were found in a vehicle belonging to the park office, it wasn’t possible to verify if the blood belonged to Billy because the vehicle was cleaned before forensic experts could examine it.

But then again, without a body, there was not much anyone could do: no one has ever been brought to justice for making someone disappear, for carrying them away. In fact, the crime of enforced disappearance doesn’t exist in Thailand.

Muenoor’s fight for justice suffered a further blow when Thailand’s Department of Special Investigation (DSI), which looks into high profile cases like those involving government officials, said they wouldn’t be taking up Billy’s case.

Meanwhile, Chaiwat, the national park chief, was promoted and moved out of the area.

The oil drum and the reservoir

But then, in an unexpected development, the DSI, under pressure from international human rights groups, suddenly announced they would start investigating Billy’s disappearance in June 2018.

Less than a year later, Muenoor received a strange phone call: investigating officers asked her to go to the reservoir in Kaeng Krachan National Park. They told her to bring incense, the smoke of which Karen people believe connects this world to the next.

When she arrived, they asked Muenoor to pray next to the water.

“Billy, if you are here under the bridge, please reveal yourself or show me a sign so that I and everyone here trying to help can bring you justice and find evidence,” she prayed. “Then we can take your case to the next step to reveal the truth about what really happened.”

With the help of an underwater robot, a team of divers set about searching the reservoir.

Image copyright GETTY IMAGES A bridge going over a reservoir in the national park

Image caption Eventually, police brought her back to the park, and to a resevoir

What they found was a rusty, 200-litre oil drum. Inside were burnt fragments of bone. That in itself was unsurprising: oil drums have been used since World War Two to torture and burn alive those who defy the government. They have become symbolic of a culture of impunity.

A DNA test indicated it was Billy inside the drum.

Afterwards, officials sent Muenoor a picture of a skull fragment – burnt, cracked and shrunken after being exposed to heat as high as 300 degrees Celsius. Whoever did this, it seemed, had tried to conceal the crime.

“What kind of person could do something like this to another person?” Muenoor asks. “It’s not human. I was devastated that he had to go through something like that. Whoever did this never thought about Billy’s family or how this would affect us. If this had happened to the killer’s family, how would he have felt?”

The game changer

In November 2019, the DSI issued an arrest warrant. It was for Kaeng Krachan National Park’s former chief, Chaiwat Limlikidacsorn, and three other park rangers. They deny any wrongdoing.

The arrest came as a shock for many in Thailand. It is unusual for someone in a senior role working for the state to be arrested on such serious charges.

And Chaiwat has made his feelings clear.

“Ever since it happened, the DSI and the media have depicted me in a negative way,” Chaiwat has complained to reporters. “It’s ruined my simple life as a government official, along with my three junior colleagues. They’ve also destroyed my family.

“Instead of being an honest government official and protecting the forest I am forced to stand in front of all of you here today. I’ve devoted my entire life, strength and energy to help this nation.”

Chaiwat and the three park rangers are charged with six offences, including premeditated murder, unlawful detention and the concealment of Billy’s body.

Enforced disappearance is not one of them.

Even so, if Chaiwat and the other park rangers are found guilty of Billy’s murder, it will be the first time one of the so-called disappeared gets justice.

Muenoor and a photo of her family

Image caption Muenoor says it has turned her world upside down

People like prominent human rights lawyer Surapong Kongchantuk believe enough pressure will be generated to force the Thai government to pass an enforced disappearance law.

“Patterns have emerged in these disappearance cases,” Mr Surapong tells the BBC. “In most cases, people disappear in broad daylight. And a lot of people are around as witnesses. But the bodies are never found, so they can’t prosecute.

“If we can find justice for Billy, this will be a game changer for Thailand.”

But while Billy’s death may change Thai law, the reason he is said to have lost his life – the fight for his village – has not been won. Even though the Karen villagers won the case against the Department of National Parks and got compensation of 50,000 baht ($1,600; £1,200) for each family, they haven’t been allowed back.

And years of struggle have taken their toll on Muenoor as well. She admits it’s been hard for the whole family to lose Billy, especially the children.

“His case was on the news so much that one day they asked me how come the person who did this to our dad isn’t in jail? What did dad do to him? Why did he have to kill dad?” Muenoor says.

“It’s been difficult. I’ve had to stay strong. I have to take care of everything at home. I have to work to earn a living, and on top of that I’m still trying to get justice for Billy. When he was still here, he supported me.

“My life has turned upside down, from day into night. —- By Chaiyot Yongcharoenchai, BBC

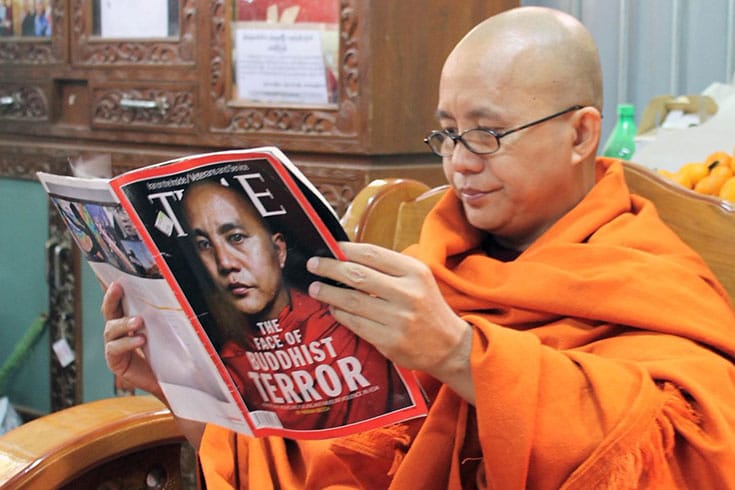

A column in “The Myanmar Times” asked readers to guess the author of a xenophobic comment: Donald Trump or Ashin Wirathu, the man known as “The Buddhist Bin Laden,” pictured above reading a “TIME” magazine article about himself. Photo by

A column in “The Myanmar Times” asked readers to guess the author of a xenophobic comment: Donald Trump or Ashin Wirathu, the man known as “The Buddhist Bin Laden,” pictured above reading a “TIME” magazine article about himself. Photo by