New Delhi: As India mulled over the possible ways to bring back IAF Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman, Pakistan on Thursday said it will decided on according the air force pilot prisoner of war status “in a couple of days”.

“India has raised the matter of the pilot with us. We’ll decide in a couple of days what convention will apply to him and whether to give him Prisoner of War status or not,” Pakistani media quoted the country’s Foreign Office spokesperson Muhammad Faisal as saying.

The 38-year-old was captured by Pakistan on Wednesday after his MiG-21 Bison crashed during an aerial dogfight with a Pakistani jet.

‘The Missing 54’

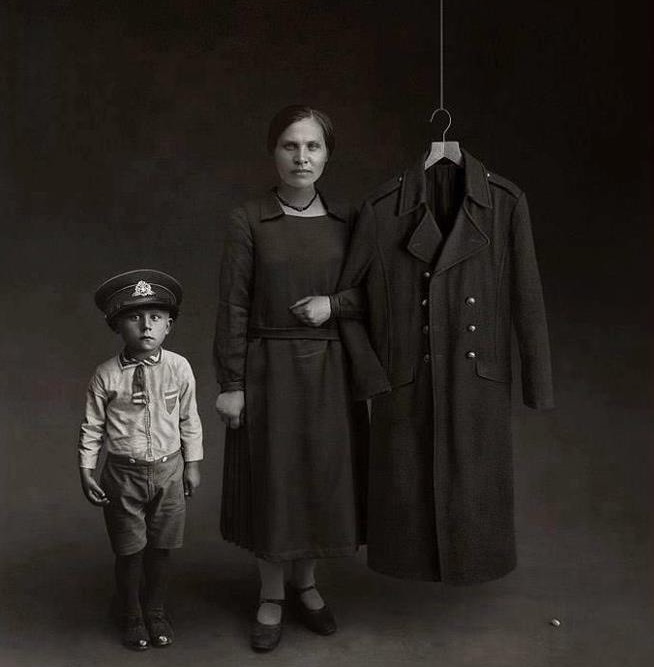

While the debate over POW status to Varthaman escalates, 54 other Indians soldiers, officers and pilots continue to be held by Pakistan as POWs since the 1971 conflict, although the Pakistan government has often denied their presence on its soil. The 54 POWs have come to be known as ’The Missing 54’.

‘The Missing 54’ are the soldiers and officers of Indian armed forces who were given the status of missing in action (MIA) or killed in action after the 1971 Indo-Pak war. However, they are believed to be alive and imprisoned in various Pakistani jails. They include 30 personnel from the Indian Army and 24 from the Indian Air Force (IAF).

The 30 Army personnel include one Lieutenant, eight Captains, two Second Lieutenants, six Majors, two Subedars, three Naik Lieutenants, one Havaldaur, five gunners and two sepoys from the Indian Army. The remaining 24 from the Indian Air Force include three Flight Officers, one Wing Commander, four Squadron Leaders and 16 Flight Lieutenants.

This list was tabled in the Lok Sabha in 1979 by Samarendra Kundu, Minister of State of External Affairs, in reply to a question raised by Amarsingh Pathawa.

The families have approached both the United Nations and the International Committee for the Red Cross in their 48-year-long campaign, but neither body was able to offer assistance.

On the contrary, during the 1971 war, India had taken almost 90,000 Pakistani troops as POWs. However, all of them were released as part of the Simla peace agreement.

Until 1989, Pakistan had completely denied holding the prisoners. However, then prime minister Benazir Bhutto finally told visiting Indian officials that the men were in Pakistani custody. The POW issue had also figured in the discussions between Bhutto and then prime minister Rajiv Gandhi during their meeting in Islamabad in December 1989. She had also assured Gandhi that she would “seriously look into their release”.

Years later, former Pakistan president Pervez Musharraf back-tracked on this, formally denying their existence in Pakistan.

However, there has been compelling evidence of the presence of 54 POWs in Pakistan’s custody.

In 1972, Time magazine published a photo showing one of the men behind bars in Pakistan. His family believed he had been killed during the war, but instantly recognised him, The Diplomat reported in 2015.

In her biography of Benazir Bhutto, British historian and former BBC correspondent Victoria Schoffield reported that a Pakistani lawyer had been told that Kot Lakhpat prison in Lahore was housing Indian prisoners of war “from the 1971 conflict”.

Victoria Schofield in her book Bhutto: Trial and Execution also wrote, “Besides these conditions at Kot Lakhpat (jail), for three months Bhutto (Zulfikar Ali Bhutto) was subjected to a peculiar kind of harassment, which he thought was especially for his benefit… His cell, separated from a barrack area by a 10-foot-high wall, did not prevent him from hearing horrific shrieks and screams at night from the other side of the wall. One of Mr Bhutto’s lawyers made enquiries among the jail staff and ascertained that they were in fact Indian prisoners-of-war who had been rendered delinquent and mental during the course of the 1971 war.”

“An American general, Chuck Yeager, also revealed in an autobiography that during the 1971 war, he had personally interviewed Indian pilots captured by the Pakistanis. The airmen were of particular interest to the Americans because, at the height of the Cold War, the men had attended training in Russia and were flying Soviet designed and manufactured aircraft,” The Diplomat wrote in 2015.

On September 1, 2015, the Supreme Court also asked the Centre about the status of these 54 Indian POWs languishing in Pakistan jails since 1971.

“Are they still alive?” the Supreme Court had questioned.

“We don’t know,” Solicitor General Ranjit Kumar, appearing for External Affairs and Defence ministries, told a bench of Justice TS Thakur and Justice Kurian Joseph.

“We presume that they are dead as Pakistan has been denying their presence in their prisons,” he said.

The provisions of the Geneva conventions apply in peacetime situations, in declared wars, and in conflicts that are not recognised as war by one or more of the parties. The treatment of prisoners of war is dealt with by the Third Convention or treaty. More specifically, the 3rd Geneva Convention of 1949 lays down a wide range of protection for prisoners of war. It defines their rights and sets down detailed rules for their treatment and eventual release. International humanitarian law (IHL) also protects other persons deprived of liberty as a result of armed conflict.