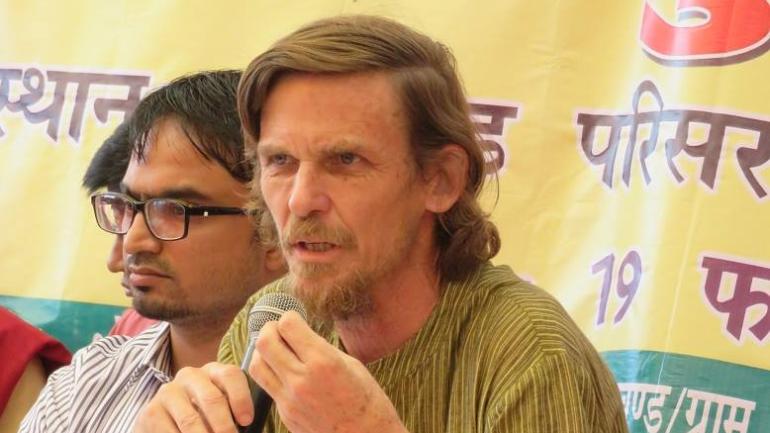

Noted development economist Jean Dreze and his associates, Vivek Kumar Gupta and Anuj Kumar Gupta, were detained by police for about two hours on Thursday just before they were about to host a public meeting in Jharkhand, allegedly without taking permission from the state administration.

The team had organised the meeting to listen to people’s grievances related to social security pensions and delayed allotment of foodgrain. After being released, Dreze said that police had threatened the organiser with legal consequences.

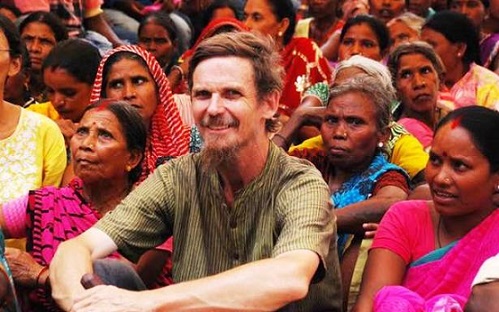

Renowned Indian development economist Jean Drèze is a Belgian-born social activist who has been influential in the economic policy making of his country. In his years in India since 1979, he has made wide-ranging contributions to development economics and public economics. He has promptly worked on social issues such as hunger, famine, gender inequality, child health and education, and the NREGA.

Jean Drèze as Academician

Born in 1959 in the ancient town of Leuven, Jean currently lives in Ranchi, Jharkhand. His father, Jacques Drèze, is one of the world’s great economic theorists and a celebrated teacher as well. Jean grew up in an atmosphere composed equally of scholarship and service. One of his brothers became a left-wing politician; a second was a professor of marketing; a third is a translator.

He studied Mathematical Economics at the University of Essex in the 1980s and did his PhD (theoretical economics of cost-benefit analysis) at the Indian Statistical Institute, New Delhi.

He has lived in India since 1979 and became an Indian citizen in 2002.

Jean Drèze taught at the London School of Economics in the 1980s and at the Delhi School of Economics. Presently, he is an Honorary Chair Professor of the “Planning and Development Unit” created by the Planning Commission, Government of India, in the Department of Economics, University of Allahabad.

He is also a visiting professor at the Department of Economics, Ranchi University.

He was a member of the National Advisory Council of India in both first and second term.

Dreze is well known for his commitment to social justice, both in India and internationally. Apart from academic work, he has been actively involved in many social movements.

He played a central role in the conception of the National Rural Employment Guarantee scheme; helped draft the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005 (NREGA), and continues to monitor its implementation.

He also contributed to the Right to Information Act and the National Food Security Act of the Government of India.

Jean has written a great deal in English. His columns have been collected in a book called Sense and Solidarity, with the self-deprecatory sub-title, Jholawala Economics for Everyone. The essays cover a wide range of themes; from food security to healthcare to the rights of children to the threat of nuclear war.

_____________________________

On the need for action-oriented research in development policy

A whole new way of looking at poverty and development policy is taking shape in the world of economics. Traditionally understood as meagreness of material resources, there is a growing realisation that poverty also depletes mental resources. Understanding of how poverty impacts behaviour, what the absence of resources does to a person’s mindset can vitaminise the poverty-fighting policy toolkit.

Insights, well-designed qualitative and quantitative data from field surveys enable sounder grasp of human behaviour. If you don’t know where your next meal is going to come from, how that makes you pick or reject an option. It is not enough to go taste the food the poor consume, visit their homes. The idea is to try to feel how being impoverished impacts decision-making and choice.

Say the task at hand is to figure out whether to universalise old-age widow pensions or not. A narrow evaluation of the proposal would measure impact on poverty of the limited version of the programme in use, the administrative costs of expanding it, the vulnerability to leakages, so on and so forth. Field intelligence could help provide the human angle such as what the pensions do to the quality of life of the beneficiaries. Being able to afford small luxuries — a new pair of glasses or treats for the grandchildren — out of the pension money rather than having to depend on their families for the expenses can improve the women’s sense of independence and dignity. The family’s attitude is also likely to become more favourable.

Economist Jean Drèze’s new book, Sense and Solidarity: Jholawala Economics for Everyone, argues for an increased role for action-oriented research in development policy. The book is a compilation of op-eds, published mainly in The Hindu, under 10 broad themes such as Drought and Hunger, Poverty, School Meals, Health Care, Employment Guarantee, and Food Security and the Public Distribution System. He has updated the pieces with introductions, background notes, statistical and bibliographic sources.

Action research is not a collection of principles, theories and methods as academic research tends to be. It supports an action, or a change, while at the same time producing new knowledge. Active cooperation between the researchers and the participants is involved in this relatively new approach. Action and academic research shares a mostly tense relationship. Action researchers see academic researchers as occupants of ivory towers.

Drèze’s argument about the inadequacies of statistical analyses and academic approaches cannot be quarrelled with. The world has grown pessimistic about economics for its over-reliance on mathematics, its failure to predict the global financial meltdown and its inability to draw the world economy out of the economic slowdown. The feel of the field gathered from his own trips far and wide, from the hills of Chamba district to the forests of Kalahandi and the dusty plains of Bihar in the book’s essays make for great reading.

Drèze’s findings from the ground leave readers less confident of imposing our assumptions about poverty and humans on policy and economics. To economists suffering from insufficient understanding of society and human life, Drèze recommends copious doses of literature (although he does also caution against getting carried away by fiction or personal experiences). The works he regards helpful in developing empathy include Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s classic novel Pather Panchali, Dalit autobiographies of Daya Pawar, Laxman Gaikwad, Om Prakash Valmiki and Shantabai Kamble.

In ‘The Bullet Train Syndrome’, he questions the pro-rich institutional bias of the Indian Railways based on his own extensive travel on its networks. “If you have money, the Indian Railways is great fun, bullet or no bullet,” he writes. “But the lesser mortal who travels without reservation is exactly where she was 35 years ago.” The book succeeds in reminding us that poverty and privilege both are inherited at birth more often than earned. “The privileged tend to believe that they deserve or have earned what they have. But the chief determinant of privilege is chance,” he writes of the accident of birth. And that often the system works to perpetuate those inequalities.

In ‘Glucose for the Lok Sabha?’, he traces the clamour from Parliamentarians and ministers for replacing cooked midday meals in primary schools with biscuits to the corporate lobby. The plea for doing away with cooked midday meals for schoolkids was first made by the Biscuit Manufacturers Association through a letter signed by a senior executive at Parle Products, the biggest manufacturer of glucose biscuits.

Drèze’s differences with academic research are deep and go beyond approach and methodology. Why is carrying a corporate briefcase innately more respectable than carrying a jhola, he asks. Jholawalas — the student volunteers, like-minded scholars, field investigators, driven by passion, not money — has become a term of abuse in India’s corporate-sponsored media, he writes.

Undeniably, corporate influence is growing. But his attack on policy and the media seem sweeping; his suspicion of intent and sense of hurt excessive. Didn’t action research play a role in the schemes he has championed: the rights-based and legislation-backed social security schemes, the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) and the Right to Food or the National Food Security Act? They too are not free of leakages and infirmities, as Drèze concedes and makes clear he would like to see the defects addressed.

Even if readers disagree with the book, it is valuable because through it Drèze hopes to start a dialogue between economists and jholawalas for greater mutual learning.

Sense and Solidarity: Jholawala Economics for Everyone; Jean Drèze, Permanent Black, ₹795.