by Simon Winchester | NYT

I had initially thought the book might be little more than an extended advertisement for Ms Lovell’s business. But then I found myself quite caught up in her infectious enthusiasm

It was in Calcutta, 40 years ago, a steaming hot Friday monsoon morning, and I had come down from my newspaper’s office in Delhi to write about the industrial tea trade. I was at the headquarters of Macneill and Magor, a tea giant of the time, whose red brick godowns lined the banks of the Hooghly River. I had a breakfast-time appointment with the company spokesman, a genial Anglo-Indian named Pearson Surita, a man possessed of an accent so plummy that on the side he did cricket commentaries for All-India Radio.

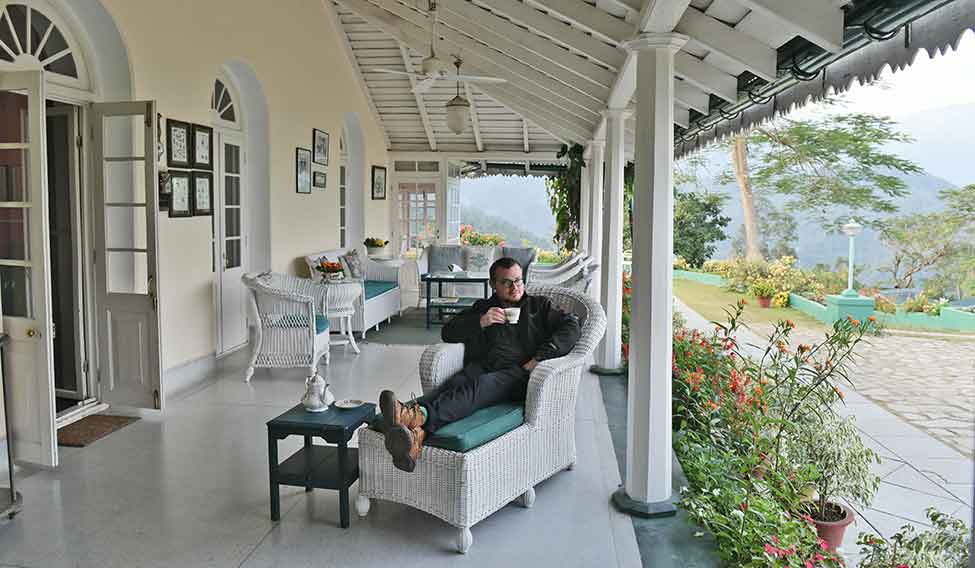

Brew and a view: A visitor at a Glenburn Tea Estate bungalow in Darjeeling.

Brew and a view: A visitor at a Glenburn Tea Estate bungalow in Darjeeling.

The elevator creaked us up to the penthouse, with its fine view of the Maidan. Pearson sat me down by his desk, then promptly called the bearer and demanded two pink gins. But it wasn’t even 8 o’clock, I protested. “Don’t worry, old boy,” Pearson replied. “It’s Poets Day.” Puzzled, I sipped timidly at my gin while Pearson threw his down in one gulp, then called the departing bearer. Another two, he demanded. I yowled still more forcefully. It was early morning. Pink gin? “Don’t be silly,” he repeated. “It’s Poets Day.”

What poet? I ventured — Yeats? Auden? Tagore (who was, after all, a Bengali). “Damn fool,” Pearson said to me genially, though by now he had turned bright red and was sweating majestically. “Poets Day here in Calcutta. Stands for ‘Piss Off Early, Tomorrow’s Saturday.’”

To Pearson, tea was merely a commodity, something that came in large chests, consisting in the main of dried black twigs, crushed by brass engine rollers after being picked in goodness knows how many dozens of estates far away in Assam and Meghalaya and Upper Burma, where the pickers lived in execrable conditions and were paid a pittance. And the customers at the other end: philistine Britons, mainly, who drank the stuff with sugar and milk and let it stew in the pot for hours. No, tea was just a job, and a job that paid nicely, though Pearson would rather have gin. He really didn’t care about tea.

But Henrietta Lovell most certainly does, and these days publicly decries those people, and those industries, whose cavalier attitude to this most divine of nectars and the Camellia strains from which it is made is, in her view, little short of sacrilege. So she is now on a holy mission to educate us all so that we can know the difference between a pu’er and an oolong, between a rooibos and a Darjeeling, and why it matters, greatly.

Ms Lovell is a hearty, galumphing Briton of good pedigree and even better connections who once worked in corporate finance in New York. But on a whim, 15 years ago, she chucked that career to start the Rare Tea Company in London and has since devoted her life to advancing the cause of leaf tea (and to denouncing that epitome of foulness known as the tea bag). More important, she busies herself promoting those farmers around the world who grow tea and tend to it with the care and compassion that so ancient and elemental a beverage deserves and rightly demands. Her visits over a decade and a half to these faraway rural geniuses are what Infused: Adventures in Tea is about.

I had initially thought the book might be little more than an extended advertisement for Ms Lovell’s business. But then I found myself quite caught up in her infectious enthusiasm as she ventured — twice defeating her own cancer, which tried in vain to slow her down — out into the world in search of the green tea hills in China, Japan and India, of course, but also in Malawi, Nepal and South Africa. On occasion, her style can be a little exhausting, with her bursts of Pete Wells-ian polychrome, but one can excuse her. This is a love letter, after all.

I read the book in one contented go on a flight from Sydney to Hong Kong, where I had a few hours’ wait before moving on to New York. Nowadays, it’s surprisingly tricky to find a good loose-tea store in Hong Kong’s vast Starbucksian airport. But it was a long layover and eventually I winkled out the shoe box of Fook Ming Tong, tucked away on an upper floor, and handed over a not insubstantial wad of folding money for a package of Lovell’s most highly recommended ambrosia: white silver tip tea from Fujian Province in southeastern China. Once home, I found myself a graduated-temperature electric kettle, as also suggested, heated fresh water to 75 degrees Celsius and infused three grams of the unprocessed leaves for 90 seconds flat. I then poured the pale and steaming liquid into two fine china cups and took them upstairs.

One careful sip, then two, then a bold draining — whereupon my wife and I declared this tea to be quite sublime, perfect, entirely unlike anything we’d ever tasted before. An impeccably caffeine-loaded, faintly perfumed start to the day. And far, far better and more efficacious in inducing wakefulness and good cheer than ever was gin, pink or otherwise, most especially when taken before breakfast.

Infused: Adventures in Tea