People and organisations in many countries around the world claim to have adopted Bhutan’s human development vision of Gross National Happiness (GNH).

However, what they actually portray is different people’s perceptions of GNH. Some are philosophical, some are well researched academic constructions, while the others are spaced-out theories.

GNH has been described as an esoteric philosophy, an inspiring concept, a developmental goal, a measure of development, a wake-up call, and so on.

It is also being criticised as a platform for ambitious politicians, a mere catchphrase, an empty promise, meaningless platitudes, a purely intellectual concept, as well as an academic redundancy.

If confusion is truly the beginning of wisdom, all these are ‘wonderful’. I, too, would like to add to the confusion by sharing my understanding of GNH, by attempting some responses and clarifications to ideas that are being exchanged.

What exactly is ‘Happiness’?

To talk about GNH, I believe that we have to first define what happiness is.

I know that the world’s greatest minds have been trying to define happiness for centuries but I have my own idea of a GNH perspective on happiness.

The happiness in GNH is not fun, pleasure, thrill, excitement – or any other fleeting emotions, it is the deeper and permanent sense of contentment that we consciously or, in our sub-conscience, seek.

Have we achieved GNH in Bhutan? The answer is ‘No’. But has GNH had an impact on Bhutanese society? Yes.

Everyone who has visited Bhutan senses a different atmosphere from the moment he or she arrives. I believe that this sense comes from the values that have been nurtured over the centuries.

Today, we are calling it GNH, therefore, I offer my understanding of GNH as it exists today.

I see GNH in four forms – the intuitive, the intellectual, the responsibility and the emerging global.

The intuitive

First of all, I see intuitive GNH values in past generations of Bhutanese who had strong mutual understanding and enjoyed interdependent existence as members of small rural communities.

The village astrologer, the lay monk, the lead singer, the carpenter, the arrow maker, the elders and the youth, all of them had their own responsibilities.

The values, drawn from Buddhist teachings, from the experience and wisdom of our ancestors and from the very practical needs of a subsistence farming lifestyle, inculcated a reverence for an interdependent existence with all life forms, or all sentient beings.

Some examples of these are seen in the reluctance to hunt and fish (both of which are banned in the country), the sometimes frustrating tendency to be less ‘productive’ to avoid hurting or upsetting someone, and putting up with the cacophony of an unruly stray dog population. To put it simply, people basically identified with their own priorities in life.

In the 1980s, farmers of one village were taught successfully to do a double crop of paddy, meaning that they doubled their rice production that year.

However, they refused to do it the following year because, as one farmer said, “We did not have time to play archery, to enjoy our festivals or to bask in the sun.”

The philosophical

Another perception level I see is the attempt to define, explain and measure GNH, along with the academic construction of the concept.

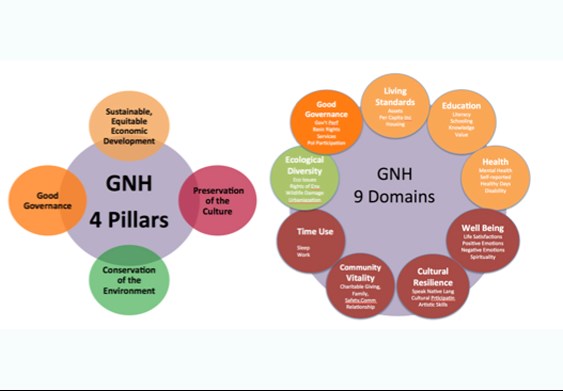

The four pillars and nine domains of GNH

As discussed earlier, the best accepted definition of happiness is the abiding sense of inter-relatedness with all life forms and of contentment that lies within the self.

This is related to the happiness that Buddhists seek from the practice of meditation.

In one understanding of GNH as a development vision, a representative of the UN Development Programme (UNDP) described it as a much more advanced concept of the Human Development Index that the UNDP has been refining.

The responsibility

This takes me to the third perception: GNH as a government responsibility.

As discussed, I think the definition of happiness as the abiding sense of contentment as well as GNH as a government responsibility make basic sense, although the translation of these into policy, legislation and prioritised activities is very much still a work in progress.

In other words, we may agree on goals, values, and responsibilities, but differ sharply on the best strategies to achieve these goals.

And yet, it is the recognition that GNH must be the basis of mainstream policy thinking that sets Bhutan apart from some countries that have expressed interest in harnessing the values of GNH.

As we have seen during the GNH conferences in Thailand, Brazil, and Canada, some people doing good work among their communities, such as the NGOs and civil society organisations, thought that they have found an identity in GNH.

In Bhutan, however, the four pillars and nine domains of GNH have given politicians and bureaucrats some idea of national priorities.

This is useful because public servants do not intellectualise policy but make decisions that have an impact on all citizens.

The international discourse

The fourth perception level is the “internationalisation” of the GNH discussion.

(Source: Chencho Dorji)

Bhutan has certainly not worked out the solutions to the world’s problems, but I think we have opened up an amazing conversation and we need to give this conversation coherence and direction.

The concept of GNH, even partially understood, excites and inspires people. After five international conferences on GNH and the April 2 meeting in New York, one criticism at home has been – stop preaching GNH overseas and make it work in Bhutan.

This is a resounding example of the need for clarity in GNH thinking and understanding. Here, I emphasise the point that we are not preaching to anyone, rather, we ourselves are learning.

There is a vast amount of research, analysis and experimentation done on GNH-related issues such as sustainability, well-being, climate change and much more, by intellectuals including Nobel laureates, by universities and institutions and by civil societies.

Bhutan must learn from them to in order to deepen its own understanding of GNH.

International discourse can only benefit Bhutan because we ourselves do not have the capacity to undertake the necessary research and analysis required to implement the tenets of GNH fully at home.

In conclusion, there is a growing understanding of, and even fear that the human population, driven by the values of GDP, is literally consuming the earth.

That is why GNH is a pun on GDP which used to be known as Gross National Product. The loud message is that human development needs a higher goal, that is, beyond GDP.