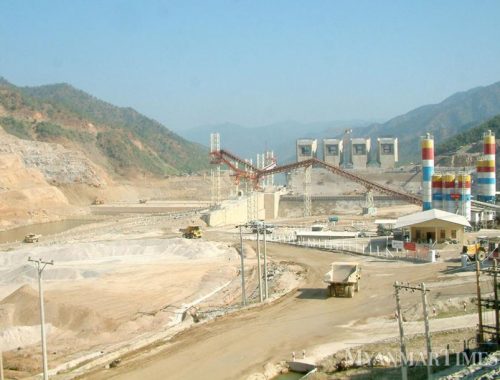

On 30 September, 2016, China announced that it has blocked the Xiabuqu river as part of a major hydroelectric project, the Lalho hydroelectric project at Shigatse. Xiabuqu is a major tributary of the Yarlung Tsangpo, the upper stream of the Brahmaputra river flowing from Tibet. The Lalho project has an investment of $4.95 billion and construction is scheduled to be completed by 2019.

It is designed to store up to 295 million cubic metres of water and will help irrigate 30,000 hectares of farmland. The strategic value of the Lalho project lies also in the fact that Shigatse is only a few hours driving distance from the junction of Bhutan and Sikkim, and the city from which the Chinese plan to extend their railroads to Nepal.

The project, however, has raised concerns in the lower riparian states of the Brahmaputra—India and Nepal. While insisting that the project is a run of the river project, the Chinese official news agency Xinhua clarified that the construction of the project will not impact water levels in the lower Brahmaputra. Yet, in the absence of a comprehensive water treaty between China and India, the construction of this dam has raised new concerns.

Since 2013, China and India have been sharing water details through an expert level mechanism which coordinates on trans-border rivers. The construction of this dam, however, raises new issues about the efficiency of the expert level mechanism.

The concerns of India are in essence threefold. The first is the traditional question of water itself. When rivers are trans-boundary in nature, lower riparian states are always at a disadvantage. This is because upper riparian states can restrict the flow of the water and effectively curtail the water rights of the lower riparian states. In this particular case, however, the issue is not limited to the Lalho project alone. This project is only a pointer of how it might affect the Yarlung Tsangpo/Brahmaputra river system in the years to come.

Both India and China have embarked on a massive hydropower energy generation path; yet in the quest for lower carbon footprint, such a race might completely destroy the ecosystem of the rivers. China plans to construct over 40 dams on the Yarlung Tsangpo. If it achieves this, the character of the river will be permanently altered. These dams could alter the geographical character as well for they are being built on slopes with a gradient of as much as 60 degrees and on the meeting point of three of the youngest mountain systems in the world. If a major earthquake were to hit the mountains, millions of people would lose their lives. The Kedarnath disaster of 2013 in India is a grim reminder of the dangers in trying to tame the Himalayan river systems.

The second concern is the character of the Brahmaputra itself. The rivers of the Himalayan ecosystem are younger and, by character, adventurous. In the last 250 years, the Brahmaputra has changed its course a number of times. The char areas in Assam are fascinating examples of this phenomenon. Every few years, new islands appear in the Brahmaputra while old ones disappear. The inhabitants of the old islands are often unsure of the country they belong to. This often gives rise to political unrest in northeastern states. Any move to control or shift the Brahmaputra course might accentuate the political problems in the north-east.

The third concern is the larger role that the river plays in the life of people in the north-east. A number of tribes have built a livelihood around the course of the river. They centre their lives around fishing and other activities. For example, lumberjacks from Arunachal Pradesh cut logs in the mountains and transport them through the Gai, Ronganodi and Subhanshiri rivers (all tributaries of the Brahmaputra) via rafts. It makes for a fascinating sight when people sail on rafts for days till they reach the plains with logs tied to the bottom of their rafts. The influence of these rivers in the lives of the people is immense.

The way forward then is to engage in a comprehensive dialogue. While the 2013 expert level mechanism was a much warranted step, much more needs to be done. Both India and China have set up aggressive goals for themselves in combating climate change. Shifting from non renewable energy sources to renewable ones like hydroelectricity is an important step in this direction.

However, as global evidence has shown us, large dams are not the solution to energy sources. Constructing continuous run of the river dams will damage the ecology of the river too. A river is not only the water body but a complete ecosystem including flora and fauna. Dams in large numbers damage this ecology. All stakeholders have to realise this. China has to take India into confidence because rivers shouldn’t be used to further political or geostrategic agendas. There is the ecological and environmental question which should be approached through consensus. Rivers are a common heritage to be nurtured by all.

The writer is assistant commissioner of income tax. Views expressed are personal

On 30 September, China announced that it has blocked the Xiabuqu river as part of a major hydroelectric project, the Lalho hydroelectric project at Shigatse. Xiabuqu is a major tributary of the Yarlung Tsangpo, the upper stream of the Brahmaputra river flowing from Tibet. The Lalho project has an investment of $4.95 billion and construction is scheduled to be completed by 2019.

It is designed to store up to 295 million cubic metres of water and will help irrigate 30,000 hectares of farmland. The strategic value of the Lalho project lies also in the fact that Shigatse is only a few hours driving distance from the junction of Bhutan and Sikkim, and the city from which the Chinese plan to extend their railroads to Nepal.

The project, however, has raised concerns in the lower riparian states of the Brahmaputra—India and Nepal. While insisting that the project is a run of the river project, the Chinese official news agency Xinhua clarified that the construction of the project will not impact water levels in the lower Brahmaputra. Yet, in the absence of a comprehensive water treaty between China and India, the construction of this dam has raised new concerns.

Since 2013, China and India have been sharing water details through an expert level mechanism which coordinates on trans-border rivers. The construction of this dam, however, raises new issues about the efficiency of the expert level mechanism.

The concerns of India are in essence threefold. The first is the traditional question of water itself. When rivers are trans-boundary in nature, lower riparian states are always at a disadvantage. This is because upper riparian states can restrict the flow of the water and effectively curtail the water rights of the lower riparian states. In this particular case, however, the issue is not limited to the Lalho project alone. This project is only a pointer of how it might affect the Yarlung Tsangpo/Brahmaputra river system in the years to come.

Both India and China have embarked on a massive hydropower energy generation path; yet in the quest for lower carbon footprint, such a race might completely destroy the ecosystem of the rivers. China plans to construct over 40 dams on the Yarlung Tsangpo. If it achieves this, the character of the river will be permanently altered. These dams could alter the geographical character as well for they are being built on slopes with a gradient of as much as 60 degrees and on the meeting point of three of the youngest mountain systems in the world. If a major earthquake were to hit the mountains, millions of people would lose their lives. The Kedarnath disaster of 2013 in India is a grim reminder of the dangers in trying to tame the Himalayan river systems.

The second concern is the character of the Brahmaputra itself. The rivers of the Himalayan ecosystem are younger and, by character, adventurous. In the last 250 years, the Brahmaputra has changed its course a number of times. The char areas in Assam are fascinating examples of this phenomenon. Every few years, new islands appear in the Brahmaputra while old ones disappear. The inhabitants of the old islands are often unsure of the country they belong to. This often gives rise to political unrest in northeastern states. Any move to control or shift the Brahmaputra course might accentuate the political problems in the north-east.

The third concern is the larger role that the river plays in the life of people in the north-east. A number of tribes have built a livelihood around the course of the river. They centre their lives around fishing and other activities. For example, lumberjacks from Arunachal Pradesh cut logs in the mountains and transport them through the Gai, Ronganodi and Subhanshiri rivers (all tributaries of the Brahmaputra) via rafts. It makes for a fascinating sight when people sail on rafts for days till they reach the plains with logs tied to the bottom of their rafts. The influence of these rivers in the lives of the people is immense.

The way forward then is to engage in a comprehensive dialogue. While the 2013 expert level mechanism was a much warranted step, much more needs to be done. Both India and China have set up aggressive goals for themselves in combating climate change. Shifting from non renewable energy sources to renewable ones like hydroelectricity is an important step in this direction.

However, as global evidence has shown us, large dams are not the solution to energy sources. Constructing continuous run of the river dams will damage the ecology of the river too. A river is not only the water body but a complete ecosystem including flora and fauna. Dams in large numbers damage this ecology. All stakeholders have to realise this. China has to take India into confidence because rivers shouldn’t be used to further political or geostrategic agendas. There is the ecological and environmental question which should be approached through consensus. Rivers are a common heritage to be nurtured by all.

The writer is assistant commissioner of income tax. Views expressed are personal