![Myanmar: Defending genocide at the ICJ Myanmar's leader Aung San Suu Kyi attends a hearing of the genocide case against the Rohingya minority at the International Court of Justice in The Hague on December 11, 2019 [Reuters/Yves Herman]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/imagecache/mbdxxlarge/mritems/Images/2019/12/22/3373f1a095024e51b1c1af52e4629a18_18.jpg)

On December 9, the world marked the anniversary of the adoption of the 1948 UN Genocide Convention: a covenant signed in the wake of the Holocaust not only to punish genocide but to prevent it.

And yet, the tatters of the shredded promise of “never again” were on display the very next day at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which from December 10 to 12 held its first hearings in the case against Myanmar for the genocide of the Rohingya.

The case was brought by The Gambia, under a provision of the Genocide Convention that permits state parties to bring a case against any other party for violations, even if they themselves are not directly affected – a reflection of the extreme gravity of the crime.

The hearings – in which The Gambia requested “provisional measures” to mitigate further deterioration of the Rohingya’s situation while the wheels of justice grind slowly forward – were just the preliminary stage of a long process which will take several more years to determine whether Myanmar bears state responsibility for genocide.

It has been 41 years since Operation King Dragon, the Myanmar military’s first campaign of mass expulsion and terror against the Rohingya; 37 years since the Rohingya were stripped of citizenship, despite being recognised as indigenous to Myanmar by Prime Minister U Nu in 1948; 31 years since military leaders developed the plan to supplant Muslim-majority Rohingya communities in Rakhine State with “model villages” for Buddhist settlers.

It has been seven years since the mass caging of Rohingya in detention camps, prompting US-based NGO Genocide Watch to issue a Genocide Emergency Alert; four years since the promulgation of “race and religion protection laws” restricting Rohingya from marrying and having children; and more than two years since the vicious, discriminatory military “clearance operations” of 2017 that drove more than 700,000 Rohingya out of Myanmar and into Bangladesh – a continuation of “unfinished business”, in the words of Senior General Min Aung Hlaing.

The Rohingya have endured massacres, apartheid, gang rape, torture, deliberate starvation, forced labour, and the targeted destruction of their homes and villages. And now, after years of international denialism, delay and indifference, they are finally having their day in court.

In responding to the accusations against it at the ICJ, Myanmar demonstrated the same callousness, cynicism, and chutzpah that characterises the output of its genocide propaganda machine. It has previously, for example, claimed that the Rohingya set their own homes on fire, that their confinement in camps surrounded by barbed wire is for their own “protection“, and that the accounts of widespread military sexual violence were inconceivable because Rohingya women are too “dirty” to rape.

The paucity and moral bankruptcy of the legal arguments in which Myanmar attempted to cloak its crimes at the ICJ only served to highlight their naked indefensibility.

For instance, Myanmar’s lawyer William Schabas critiqued the UN’s Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar, the main source for the allegation of genocide, for failing to “point to any evidence of mass graves”. Of course, the primary barrier impeding the compilation of such evidence has been Myanmar’s penchant for blocking investigators and bulldozing over atrocity sites. Despite this, the mission’s September 2018 report did, in fact, document several mass Rohingya graves, for example at Maung Nu, Gu Dar Pyin, and Inn Din.

Schabas also argued that the fact that only a portion – 10,000 – of the Rohingya population has actually been eliminated by the regime so far contradicted the inference of genocide – reducing genocide to a gross numbers game contra international law. He completely omitted to mention the unquantified thousands more who have been raped, tortured , and starved, all of which are also acts of genocide when conducted with an “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group”.

Far from disproving the genocidal nature of the state’s project against the Rohingya, Myanmar’s submissions confirmed the regime’s utter disdain for its victims.

State Counsellor and Foreign Minister Aung San Suu Kyi, representing Myanmar as its agent in the case, refused to even use the word Rohingya except when referring to the militant Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army – itself a sign of the genocidal desire to delete the Rohingya off the social, linguistic and conceptual map.

Myanmar’s official policy of erasing Rohingya identity continues through the very same refugee repatriation process repeatedly cited by Myanmar at the ICJ as proof of its good intentions. The National Verification Cards central to the repatriation scheme function as “tools of genocide” by effectively identifying the Rohingya as “foreigners”, as a recent report from human rights organisation Fortify Rights concluded.

Even as Myanmar stood before the international court denying genocidal practices, 93 Rohingya, including 23 children, were on trial in the city of Pathein for the crime of “illegally travelling” to flee what one Rohingya blogger describes as the “open concentration cell” of Rakhine.

According to Suu Kyi, however, the overwhelming state violence inflicted upon the Rohingya is nothing more than a legitimate “counter-terrorism” response to Muslim fighters linked to “Afghan and Pakistani militants”. Myanmar’s ICJ submission claims the army launched “clearance operations” after attacks on police stations and villages by the armed group Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army on August 25, 2017.

In reality, the influx of troops and various other preparations for the 2017 “clearance operations” began before the Rohingya attacks that supposedly triggered them. And an International Crisis Group report cited as Myanmar’s sole source for the connection to “Afghan and Pakistani militants” contains nothing about Afghanistan and only one passing reference to Pakistan. This report does, however, make clear that what Myanmar portrays as the Rohingya menace – the provocation for its military brutality – has consisted mostly of “ordinary villagers [armed] with farm tools”.

Just like the Uighurs languishing in the world’s largest system of concentration camps, the Kashmiris suffering under the world’s largest military occupation and the Palestinians suffocating in the world’s largest open-air prison, the Rohingya have refused to go quietly like “lambs to the slaughter“. And that refusal has been presented by their persecutors as “terrorism” justifying the butcher’s knife.

Even the paradigmatically non-violent effort to seek justice through the UN’s judicial organ, the ICJ, was depicted by Myanmar as a shadowy Islamic plot, with The Gambia accused of acting as a front for the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC).

The argument is based on neither law nor logic; The Gambia has every right – and arguably even a duty – to bring the case as a party to the Genocide Convention, and the case is supported by Canada and the Netherlands as well as the OIC. Rather, it appeals to Islamophobic conspiracy theories such as those espoused by Suu Kyi about “global Muslim power,” reminiscent of old anti-Semitic myths of Jewish world control.

Suu Kyi concluded Myanmar’s presentations to the court with two pictures of diverse ethnic groups “proud, enthusiastic, and laughing” together at a football match in Rakhine. It was the photographic equivalent of the gulag and ghetto tours staged by the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, which presented a Potemkin facade of normalcy – complete with vignettes of the condemned playing football – to conceal the horrors lying beneath.

The spectacle of a Nobel peace prize laureate covering up a genocide has transfixed the world. But the grotesque bathos of Suu Kyi emblematises the shame of the international community writ large, which poses as the guardian of peace and civilisation while allowing mass atrocities to unfold in plain sight.

There is the shame of the vast constellation of governments and corporations that continued to arm, fund and collaborate with the genocidal Myanmar military, as documented by the UN Fact-Finding Mission in a report released in September.

There is the shame of the international organisations whose “years of secrecy, self-censorship and silent compliance with government policies of abuse” in Myanmar made them “complicit in a process of preparation for ethnic cleansing”, according to a comprehensive review by veteran human rights fieldworker Liam Mahony.

And there is the shame of all the states that deferred recognising the situation as genocide to avoid activating their duty to prevent.

The present ICJ process is not a panacea for the international community’s abdication of responsibility.

The ICJ in this case only has jurisdiction over genocide – a restriction exploited by Myanmar in its submissions, which proffered the extraordinary defence that its actions may have constituted “war crimes” or “crimes against humanity” but not genocide, and therefore lie beyond the remit of the court.

Moreover, the ICJ lacks any coercive mechanism to enforce its judgements, as devastatingly demonstrated by the execution of the Srebrenica massacre two years after provisional measures were imposed in the Bosnia v Serbia case.

As international law professor Frederic Megret observes, perhaps “the best hope of averting or limiting the consequences of genocide lie with an infinity of small, local acts of resistance rather than a univocal focus on big, structural and international solutions to the problem”.

The fact that the Myanmar case has made it to the ICJ is a testament to the enduring and determined resistance of the Rohingya people and to the tireless, often perilous work of Rohingya writers, lawyers, activists and organisations, and their allies, whose efforts for justice continue both inside and beyond the court.

The Free Rohingya Coalition, for example, is currently seeking international civil society support for a boycott campaign targeting corporations complicit with Myanmar’s crimes.

With the Rohingya genocide finally on trial, now is not the time for international self-satisfaction, but reinvigorated solidarity with the victims of the world’s violated promise of “never again”.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.

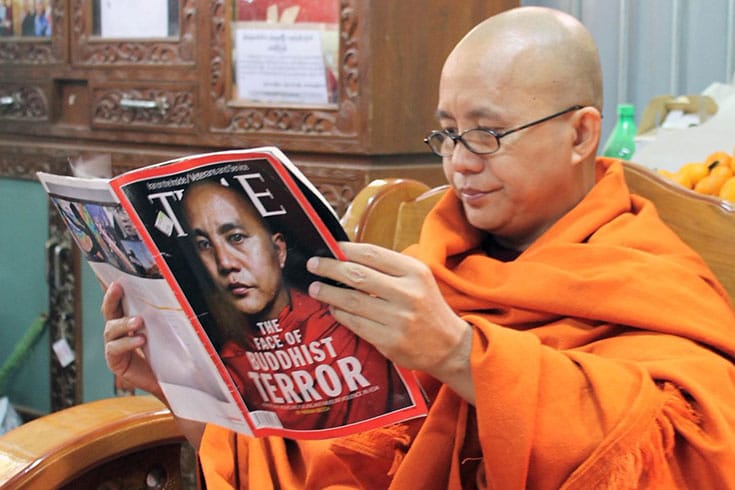

A column in “The Myanmar Times” asked readers to guess the author of a xenophobic comment: Donald Trump or Ashin Wirathu, the man known as “The Buddhist Bin Laden,” pictured above reading a “TIME” magazine article about himself. Photo by

A column in “The Myanmar Times” asked readers to guess the author of a xenophobic comment: Donald Trump or Ashin Wirathu, the man known as “The Buddhist Bin Laden,” pictured above reading a “TIME” magazine article about himself. Photo by