In Arunachal, a 1000-year-old paper-making technique turns a new page

The paper — sourced from the bark of the shugu sheng shrub — is used as manuscripts, scriptures etc in Buddhist monasteries (Source: KVIC)

When the machines — derelict due to nearly two decades of abandonment — revved to life on Christmas, Maling Gombu heaved a sigh of happiness.

It was only in February that the Tawang-based social worker and lawyer had written to the Khadi and Village Industries Commission (KVIC), the country’s premier village industries development body, bringing to its notice the potential of a rare and languishing paper-making craft of his state.

“We call it ‘mon shugu’, or the paper of the Monpa people,” says Gombu on the phone from Tawang, “This is no normal paper. It is special, has roots in a tradition that is a thousand years old, and needs to be preserved — before it’s too late,” he says.

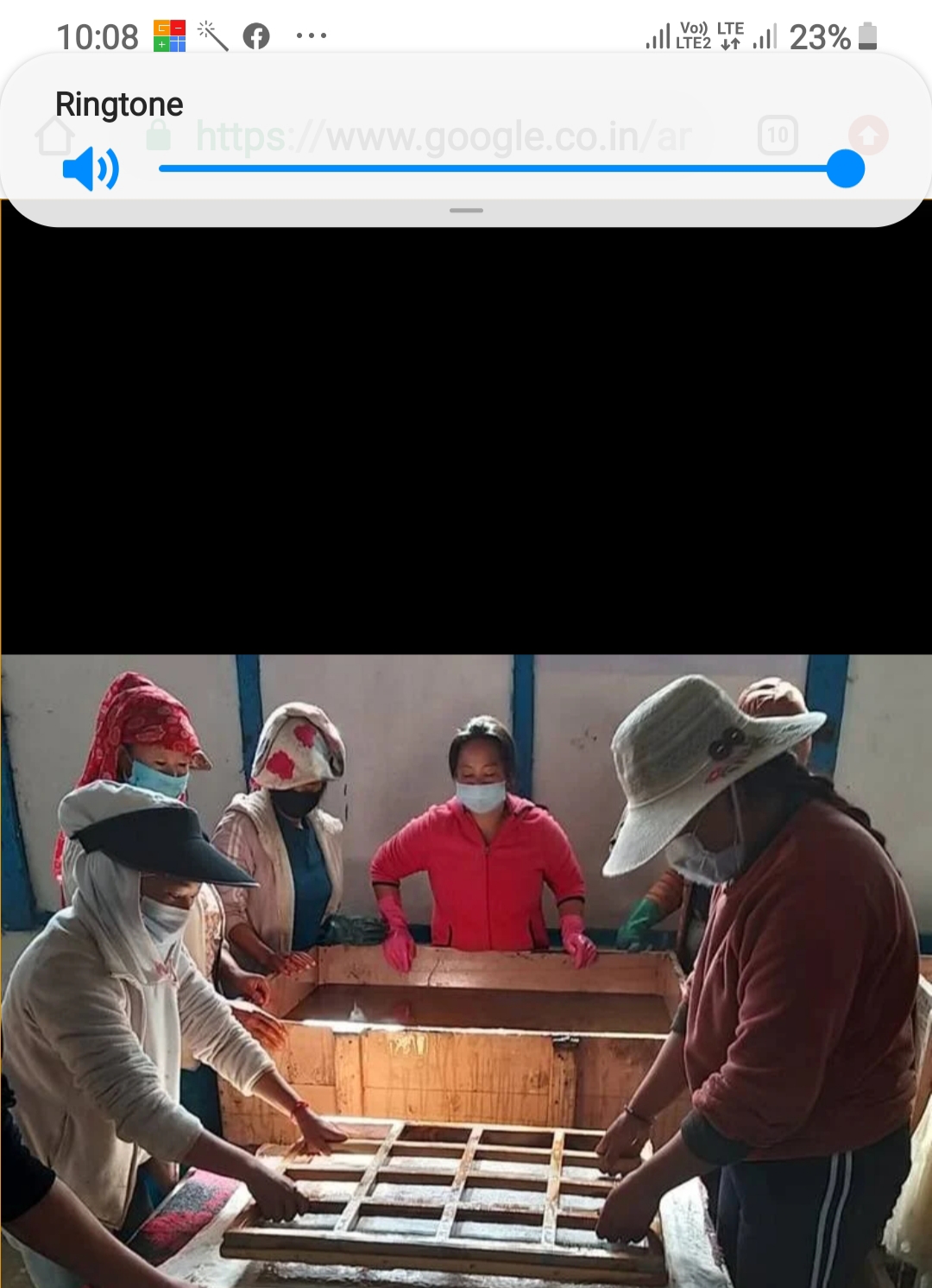

The ‘Monpa handmade paper making unit’ was inaugurated on December 25 in Tawang, Arunachal Pradesh in a bid to preserve the Monpa community’s heritage craft (Source: KVIC)

It did not take long for the KVIC to act. On December 25, after months of planning, interrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic, an abandoned government building in Tawang transitioned into the “Monpa handmade paper making unit”, employing nine local artisans to make the special paper.

In the forests of Mukto, a village perched at an altitude of 10,800 feet in Tawang district, grows the shugu sheng shrub (Daphne papyracea), the bark of which has been traditionally processed into ‘mon shugu’ by the Monpa tribe.

For centuries, the paper has made its way to the many Buddhist monasteries not just locally, but in Tibet, Bhutan, China and Japan too, where it serves as a medium for religious scriptures, manuscripts, prayer flags, and sometimes as part of flag poles and prayer wheels

Chorten Norbu, a 40-year-old school teacher from Mukto, remembers how at one point of time almost every household had a paper-making unit.

“But it was not easy to do — it was hard work, took all day, and had very little return,” he says, “Sometimes, raw materials were not easy to source, even if you got it, there was the long process of boiling, beating, drying, cutting (of paper) — all by hand. You would have to be in the hut all day for one sheet of paper.” According to Norbu, many people began to look for alternative sources of income.

Yet, the uniqueness of the craft was not lost on those who visited Mukto. Take for example, Dr Sukamal Deb, now the deputy chief executive officer, Northeast Zone, KVIC. “In 1987, I was posted in Arunachal Pradesh in the department of industries. My work led me to learn about many crafts of the region — including ‘mon shugu’,” he says.

When the official found only a handful of people were making the paper, he felt something needed to be done. Deb’s efforts led a KVIC team to study the craft, in partnership with the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), in the mid-1990s.

“Subsequently, a project was launched by the KVIC to modernise it — basically do away with the manual drudgery. A common facility centre at Mukto was made, machines were brought in to speed up the work in 2003, and a group of artisans were sent to Jaipur for a training program by the Kumarappa National Handmade Paper Institute, under the KVIC,” says Deb. “Yet for various reasons, the project just did not take off.”

And the machines — boilers, beaters and driers — lay idle in two lonely sheds in Mukto for years.

“But last year, I was speaking to Maling (Gombu) about this and suddenly we thought — why not try to revive the craft,” says Deb.

At a KVIC programme in Itanagar, Gombu met Vinai Kumar Saxena, the current chairman of KVIC and discussed the idea with him. “He was more than enthusiastic,” says Gombu, who then wrote a letter to Saxena, officially volunteering his NGO, Youth Action for Social Welfare, as a partner for the revival project. “The machines were in pathetic condition, but they were not damaged at least. So, we shifted them from Mukto to Tawang, and got them up and running,” he says.

Almost two decades ago, Deb recalls how samples of the shugu sheng bark were sent to Jaipur and Germany for testing. “The results were outstanding. Not only does the paper have huge tensile strength but is durable, and made without a single chemical additive,” he says.

A 2006 paper, “A Traditional Source of Paper Making in Arunachal Pradesh”, says the mon shugu is “strong with its visible natural fibres and a unique texture”.

“So it is not just that the process is unique, but the product is as special,” says Gombu, adding that it is for this reason that the paper serves as a good material for religious scriptures. “The bark from the shrub has to be extricated, dried, boiled with a solution of ash, made into pulp and then cut into sheets of paper,” he says.

The machines have been brought in to make the process faster. “For example, the final process, which involves drying is dependent on the sun — sometimes it may take a day to do. But with the drier, this will be simpler now,” he says.

Yet, there are hurdles. “Many communities here have local laws such as not allowing their forest produce to be taken outside the villages. So it may be difficult to ge8t an unlimited supply of shugu sheng, which grows only in certain areas,” he says.

So the efforts will focus on doubling up domestic plantations of the shrub, and finding a suitable commercial market. “And of course, there are artisans to convince, many of whom have moved away from the craft altogether,” says Gombu.

Norbu, for one, had attended the workshop way back in the early 2000s. “It didn’t work out then, so I left and became a teacher. But this time, I hope it works for the local youth and our craft is preserved for good,” he says.